“Today, all these years later, the Trump administration is much more focused on acquiring new nuclear weapons systems than constraining or eliminating them. And the White House seems all too eager to walk away from the treaties and tools that were built to reduce these weapons’ greatest risks.”

MONICA MONTGOMERY | thebulletin.org

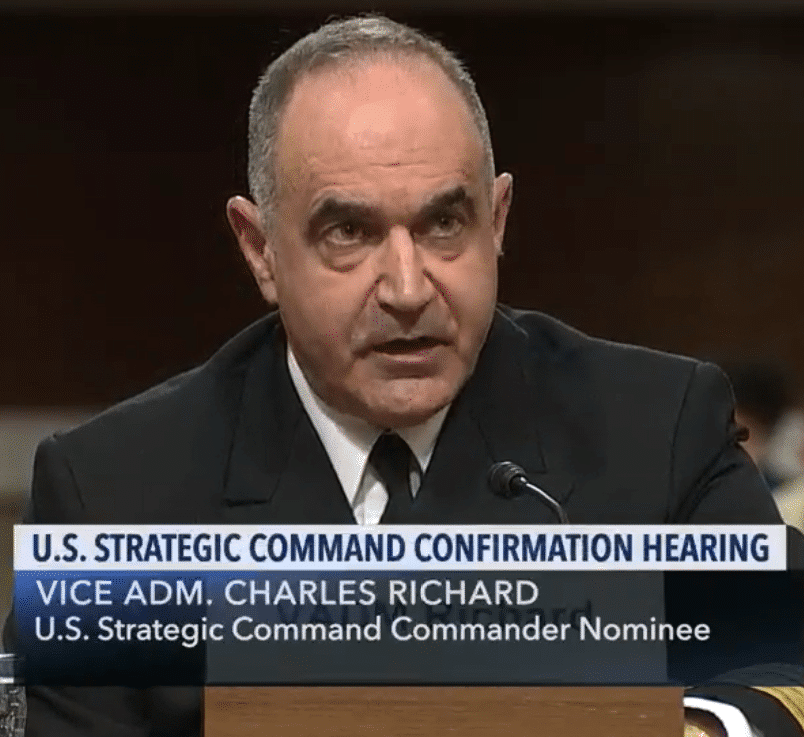

In late February, Adm. Charles Richard, head of US Strategic Command, told a House committee that the innovations going into a new nuclear warhead are what make him “proud to be an American.”

He was referring to the W93, a new nuclear warhead that will be used on submarine-launched ballistic missiles and that the Trump administration wants $53 million to start work on this year. While the design and timeline remain unclear, the administration forecasts that the price tag for developing and building this new weapon will reach over $1 billion per year in the next four years. The W93 would join or replace at least three other submarine-launched nuclear warheads that already exist and for which billions already have been and are still being spent to modernize.

The admiral’s musings about what makes him proud of his country sent me back to a conversation about nuclear weapons from just a couple weeks before. And pride certainly was not the emotion that conversation evoked.

I was attending a forum in Paris hosted by the Nobel Peace Prize-winning International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). The forum, titled “How to Ban Bombs and Influence People,” brought together students, activists, artists, and experts from across the globe. Together, they explored how to advance the cause of nuclear disarmament by building intersectionality with—and gaining insights from—other movements that address issues such as climate change, human rights, or conventional arms. (I am proud to work for one of ICAN’s US partners, the Friends Committee on National Legislation.)

ICAN had invited Setsuko Thurlow, a Hiroshima survivor and ICAN campaigner, to begin the forum. Thurlow was 13 years old when an American aircraft dropped an atomic bomb on her home city. A twist of fate put her and 30 of her classmates outside the bomb’s epicenter; over 300 of her other classmates were not as fortunate. As Thurlow says, those classmates instantly perished with “a flash of light and heat that wiped them from the face of earth.”

Thurlow recounted how she floated in the air for several seconds after the bomb’s explosion, before she lost consciousness. When she awoke, she was trapped under the rubble of a collapsed building, shrouded in silent darkness. After crawling out, she saw that the rubble was on fire and that the sky, previously flooded with the morning’s early light, had turned dark. Most of the 30 classmates with her that morning could not get out. They burned alive.

She made her way to a nearby hill. In the scene stretching before her, lifeless bodies lay strewn about, while a “ghostly” procession of survivors streamed past, their flesh burnt, swollen, and hanging from their bones.

When she reunited with her four-year-old nephew the following day, Thurlow saw how the explosion had scorched him beyond recognition. He died four days later.

Thurlow today strives for nuclear weapons’ elimination because of this image: “the symbol of innocent children of the world” who would fall victim to the next nuclear attack.

She has recounted her story thousands of times, even though she says each new telling is no less difficult. She does it to ensure that the world does not forget the pain and destruction caused by what counts as just one “small” nuclear weapon by today’s standards.

Her testimony elicited sorrow, followed by bewilderment, frustration, and indignation. These are the emotions that all the stories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki survivors elicit.

Testimony by the commander of my country’s nuclear forces should not do the same. Yet, bewilderment, frustration, and indignation are exactly what I feel when I hear a new nuclear warhead hailed as a source of national pride. All this, and sorrow too.

Billions of dollars for yet another nuclear weapon that would make, in Thurlow’s haunting words, “the living envy the dead” do not make me proud.

Decades of irrevocable degradation and radiation that nuclear weapons has inflicted—and is still inflicting—on marginalized communities and our shared environment do not make me proud.

Images of a 13-year-old trapped under piles of debris or a 4-year-old burned beyond recognition do not make me proud.

I understand how a leader might draw satisfaction from a talented, well-trained team coming together to accomplish a feat of engineering. But how sad it is to then realize that those efforts were spent in pursuit of a weapon whose explicit purpose is to threaten future 13-year-olds with the same tragedy that Thurlow and her classmates suffered.

This year will mark the 75th anniversary of the bombing that so altered Thurlow’s life—and ended hundreds of thousands of others. It also marks 50 years since the United States helped bring into force the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), aiming to constrain and ultimately eliminate the dangers that this new type of weapon poses.

Today, all these years later, the Trump administration is much more focused on acquiring new nuclear weapons systems than constraining or eliminating them. And the White House seems all too eager to walk away from the treaties and tools that were built to reduce these weapons’ greatest risks.

I take pride in the decades-long work on arms control that the Trump administration now seems intent on wasting. However halting and insufficient it may have been, Americans used the NPT and other arms control measures to try to overcome the fearsome threat to humanity that nuclear weapons pose. And I am determined to see the United States leading in the work to finally eliminate them once and for all.

Now that would be something to be proud of.