The Santa Susana Field Laboratory site is “one of the most toxic sites in the United States by any kind of definition,” Jared Blumenfeld, head of the California Environmental Protection Agency, told me. “It demands a full cleanup.”

BY: MICHAEL HILTZIK

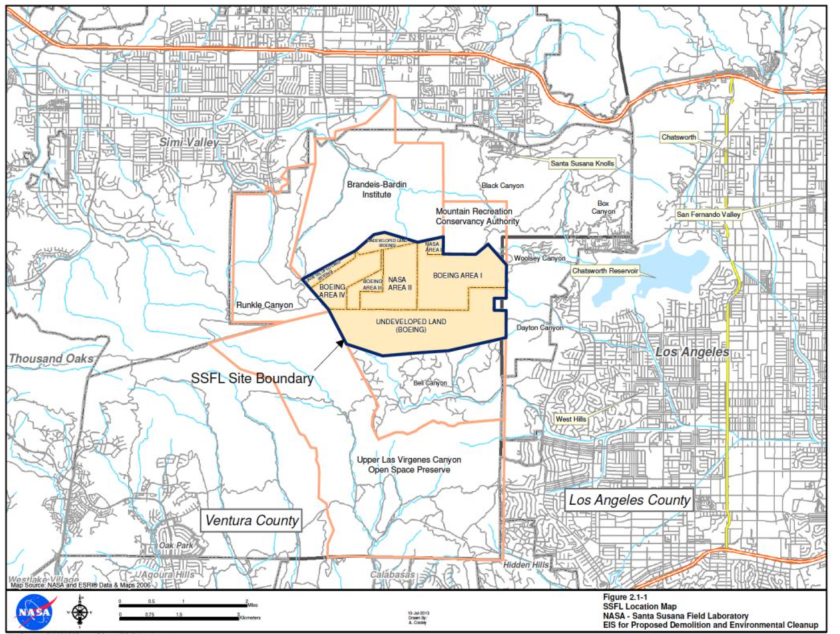

One thing is certainly true about NASA’s curious effort to place 2,850 acres above the Simi Valley on the National Register of Historic Places: The parcel is certainly a landmark.

Among the points in dispute is what makes it so.

To several local Native American tribes, including the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians, the Ventura County site’s cave drawings and rock shelters bespeak a cultural heritage dating back centuries.

The time has come for us to make sure that we hold the polluters accountable for their legacy….We will make sure the site gets cleaned up and we will exercise our legal authority in pursuit of that. – CALEPA SECRETARY JARED BLUMENFELD

To environmentalists and the site’s neighbors, it’s historic for the extent of its contamination by chemical and nuclear research performed there during the Cold War.

The Santa Susana Field Laboratory site is “one of the most toxic sites in the United States by any kind of definition,” Jared Blumenfeld, head of the California Environmental Protection Agency, told me. “It demands a full cleanup.”

Just such a cleanup should have been started years ago. The three entities controlling portions of the site — Boeing Co., the U.S. Department of Energy and NASA — reached agreements with the state in 2007 and 2010 binding them to restoring the site to “background” standards.

The term means removing contaminated soil and buildings so thoroughly that the area would be as pristine as if the polluting activities had never occurred.

It was a mix of luck, strict health guideline enforcement and one helpful QR code.

That work was supposed to be completed by 2017. Yet much of it has not even started — and it may be thrown into further doubt by NASA’s nomination of the site to the historic register.

Why the cleanup has been stalled isn’t entirely clear, although one obstacle has been the state’s failure to complete an environmental impact report for the cleanup.

The report is a highly technical document on which public comments are still being collected, according to Meredith Williams, director of the state Department of Toxic Substances Control, which is overseeing the process. Williams says the document is now expected to reach completion next spring or summer.

Instead of establishing the government’s responsibilities conclusively, the 2007 and 2010 agreements became part of the battlefield trod over by state and federal agencies. As recently as Sept. 28, the DTSC crisply informed NASA that its published plans for a reduced cleanup violate the agreement.

The state agency “strongly urge[d]” NASA not to issue a formal announcement of the plans. Four days later, NASA did so anyway.

Santa Susana deserves to be recognized as another example of how powerful interests manage to dodge their responsibilities to clean up after themselves by exploiting legal delays and loopholes, to the detriment of local communities.

It’s on a par with the successful effort of Exide Technologies to avoid paying for the cleanup of pollution it caused around its battery recycling plant in Vernon, which we recently chronicled. That case involved a private firm. This one is even worse, because the entities dodging their responsibilities include agencies of the federal government.

The historical nomination by NASA, says Daniel O. Hirsch, a former environmental faculty member at UC Santa Cruz who has been following the Santa Susana saga for some 40 years and serves as president of the Committee to Bridge the Gap, an anti-nuclear group, could save Boeing, NASA and the Department of Energy hundreds of millions of dollars in cleanup expenses.

“The only people who would lose would be the public,” Hirsch says. “They would continue to face elevated cancer risk from contamination” migrating from the site.

The tribes have said in video statements that a historical designation need not interfere with the cleanup, but such a classification will give them a say in how it proceeds.

To understand the gravity of the situation — and why local residents remain agitated about the delay’s implications for their health — let’s consider the site’s noxious condition.

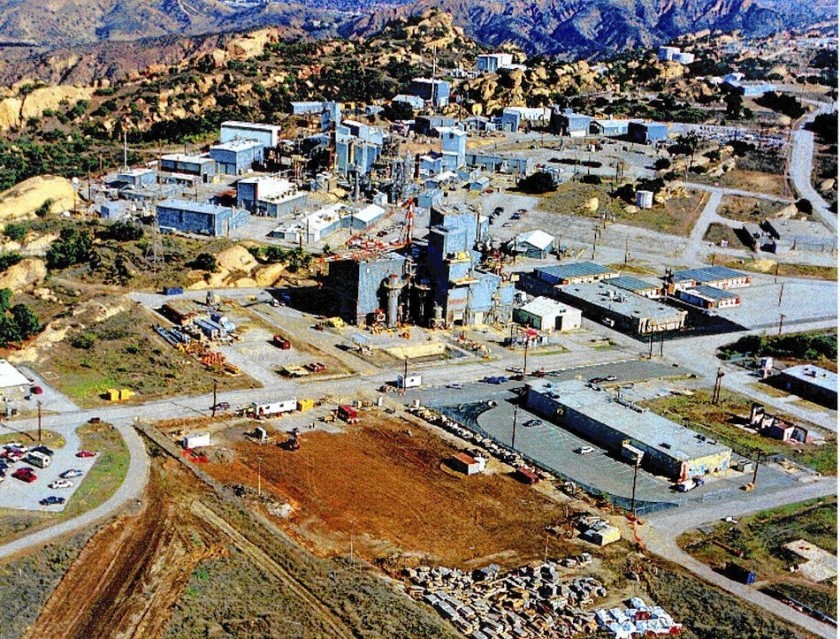

Over a period of 75 years, the Santa Susana Field Lab hosted what the Natural Resources Defense Council says were “hundreds of nuclear and rocket testing buildings and structures,” emitting radioactive isotopes including plutonium-239.

The soil and water table were contaminated by PCBs, heavy metals, tricholoroethylene “and a witches’ brew of other poisons,” as the NRDC put it.

Nuclear reactors at the lab suffered at least four major accidents between 1959 and 1969, including one partial meltdown, two episodes of fuel damage and a separate release of radioactive gases. The government typically kept these incidents secret for weeks, sometimes longer.

In a 2007 paper, researchers at the University of Michigan found the incidence rate of certain cancers, including thyroid, bladder and blood system cancers, to be more than 60% higher for residents living within two miles of the site in 1988-95 than for those more than five miles away.

The document that NASA filed this summer nominating the site for the National Register of Historic Places glosses over this history as though it never happened.

Absurdly, the nomination states that despite the activities of the government and Boeing, the area is “in a state similar to when the [tribes’] ancestors used and occupied the area.”

This summer, NASA nominated the lab site for inclusion on the national landmark registry, under the name Burro Flats Cultural District, citing its rich tribal history. A 12-acre portion of the site, encompassing the Burro Flats painted cave and a parcel traditionally used by Native Americans to observe the winter and summer solstices, has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1974. NASA asserts that its archeological research justifies expanding the landmark to encompass the entire laboratory site.

Then, on Oct. 2, the agency formally announced that it was considering a scheme to clean up the site to only a fraction of what is required by the 2007 and 2010 agreements. That flouted the state’s Sept. 28 warning not to do so, lest it result in “necessary actions to enforce” the agreements.

The historical nomination is opposed by the Ventura County Board of Supervisors, the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Committee to Bridge the Gap generally because they see the move as subterfuge through which NASA can slink away from its cleanup responsibilities.

Given this chronicle, it’s hardly surprising that any action by the government inspires skepticism.

“NASA and the DOE have a mixed history, to be polite, and the neighborhood distrusts them immensely,” says Sam Cohen, a legal advisor to the Chumash tribe.

“It’s going to take years to clean up the land,” Cohen says. “We need to be at the table at the beginning or we’re going to be disappointed at the end.”

There are, as it happens, plenty of grounds for distrust. One is that the boundaries of the nominated land correspond exactly to the Santa Susana Field Lab property lines, even though it’s rare that any historical site be chosen with regard to ownership boundaries.

Another is that the proposed designation tracks suspiciously closely to a provision in the 2010 agreement reached by the federal government and the state, exempting from cleanup “Native American artifacts that are formally recognized as Cultural Resources” — which is what NASA is requesting.

These factors and others prompted the NRDC and Committee to Bridge the Gap to warn the state Historical Resources Commission, which must rule on any federal nomination to the historical register, that NASA’s move is “an attempt by the Trump administration to breach the SSFL cleanup agreements.”

Yet the commission bulled ahead, debating the issue at a meeting Aug. 14. At that meeting tribal representatives supported the nomination while a representative of the Ventura County Board of Supervisors, Hirsch and members of Hirsch’s group all spoke against it.

A NASA representative told the commission, however, that the proposed designation wouldn’t affect the cleanup at all. “NASA continues to be committed to a cleanup at Santa Susana Field Lab,” she said. The commission, apparently mollified, endorsed the designation unanimously.

But NASA’s critics noticed that the NASA representative, Rebecca Klein, chose her words carefully. “She said they were committed to ‘a cleanup,’” Hirsch observes. “She didn’t say they were committed to the 2010 agreement.”

NASA told me by email that the cleanup standards embodied in the agreement are not “scientifically and technologically achievable.” The standards cannot be met “even if we backfill all removed soil with the store-bought topsoil many of us use in our own yards and gardens,” agency spokeswoman Shannon Segovia told me. The agency says its proposed cleanup would remove up to 90% of the contamination as the agreement requires but involve removal of 70% less soil.

CalEPA’s Blumenfeld says the decision of how to perform the cleanup isn’t up to NASA. “The 2007 and 2010 agreements are legally binding and don’t leave a lot to the imagination,” he says. “They’re very descriptive and prescriptive to infinitesimal levels of detail.”

He adds that the government’s approach to Santa Susana is oddly bifurcated. The Department of Energy, which is largely responsible for the nuclear cleanup, has been relatively cooperative, having started to dismantle the radioactively contaminated buildings on the site.

NASA, however, “is in the camp of trying to spend as little money as possible to do as little work as possible.” It may see its historical nomination as a tool to undermine the 2010 agreement, “but it’s not going to achieve that,” Blumenfeld says.

As for Boeing, which inherited its share of the cleanup in 1996 when it acquired Rockwell International’s aerospace and defense businesses, also has dragged its feet, but its responsibility is currently subject to court proceedings.

All this leaves unexplained how ironclad legal agreements could be flouted with impunity for a decade or more. In the past, blame has settled upon the Brown administration for failing to pursue the cleanup aggressively.

Blumenfeld says that era is over. He says all the parties should understand that “we’re very serious about implementing the legally binding agreements and about our regulatory authority. … There’s this bizarre time in history that we’re trying to explain no longer exists where NASA feels like they get to set the cleanup standards and Boeing feels they get to set the cleanup standards.”

For years, he says, “there was the sense by the polluters that trying to push back would save money on the cleanup.” Polluters shirking their cleanup responsibilities is nothing new, he adds.

“The time has come for us to make sure that we hold the polluters accountable for their legacy. … We will make sure the site gets cleaned up and we will exercise our legal authority in pursuit of that. That hasn’t been the message that they’ve heard for the previous 10 years, but we’re changing it.”

Will that happen? Let’s hope that we don’t have to wait another 10 years to find out.