“Given LANL’s history it’s imperative that monitoring be robustly resumed,” Jay Coghlan, Executive Director of Nuclear Watch New Mexico, said in an email. “This is after all the Lab that use to claim that groundwater contamination was impossible… Now we know of heavy chromium and high explosives groundwater contamination which are a harbinger for more contaminants to come.”

BY: ERIC MACK | forbes.com

Town of Los Alamos, New Mexico on the left and center, the Omega Bridge in the middle and the Los Alamos National Laboratories on the right. GETTYWhen the coronavirus and resulting Covid-19 pandemic closed everything in mid-March, TA-54 was one of the many places where all activity came to a virtual standstill.

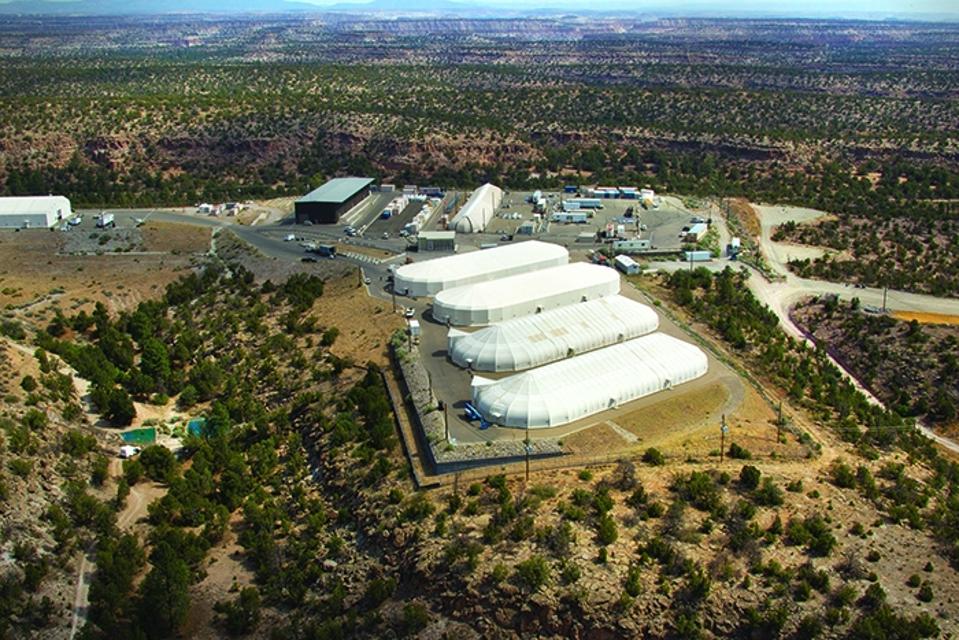

Technical Area 54 is a part of Los Alamos National Labs (LANL) in New Mexico – the same Los Alamos that was home to the Manhattan Project, which ushered in the atomic era and today continues to produce radioactive triggers for nuclear weapons.

Within TA-54 is what’s called Area G. The federal government refers to as LANL’s “legacy waste management area.” For over 60 years, it has been a storage, processing and disposal area for different kinds of radioactive and otherwise toxic waste from LANL.

TA-54 and Area G occupy a strip of high desert scrub-land in between the main lab facilities and the bedroom community of White Rock. And all the places I’ve mentioned so far sit on top of the Pajarito Plateau overlooking the mighty Rio Grande river and the city of Santa Fe in the distance.

Earlier this month the US Environmental Protection Agency provided me with a list of sites across the country that suspended normally required monitoring and reporting of what they discharge into local watersheds under the Clean Water Act. Facilities with discharge permits were allowed to pause their water pollution reporting, beginning in March, under a temporary policy that halted enforcement of the country’s major environmental laws due to the coronavirus pandemic.

The list included a number of recognizable facilities, like Boston’s Logan International Airport, a number of water pollution control plants around New York City, coal mines, lumber mills, recycling facilities, hospitals, schools and even a Waffle House in Louisiana.

But the four characters from the list of 352 non-reporting facilities that jumped out at me were: TA54.

TA-54 and Area G are specifically listed among the polluting sites across the country that went un-monitored for nearly three months this year while humanity shifted its attention to Covid-19.

I thought about the site, perched atop the Rio Grande, adjacent to the San Ildefonso Pueblo and near the Buckman well system that provides Santa Fe with much of its drinking water.

I’ve stood on the banks of the Rio Grande next to the Buckman facility and looked up at the Pajarito and White Rock above. It’s a quiet, beautiful place. And it’s easy to see how anything from up there could make its way down to one of the continent’s most important rivers very easily with a little help from the annual monsoon rains or seasonal snow melt.

Newport News Nuclear BWXT Los Alamos (N3B), the contractor that manages the clean-up of TA-54 in cooperation with the Department of Energy and LANL told me that those operations “were reduced to Essential Mission Critical Activities (EMCA) on March 24, 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.”

“As a result, most… field work was suspended at the time, includ(ing) the majority of the groundwater and surface water monitoring work. The suspension of these field activities presented no risk to human health or the environment.”

The New Mexico Environment Department (NMED) also does its own air, water, soil, sediment and biota testing to check for signs of contamination from the lab, but that monitoring was also put on hold in mid-March and is just beginning to restart as the summer monsoons are now taking hold.

“Groundwater samples will most likely be made up for as N3B personnel play catch-up to ensure that all wells are sampled before end of the Federal Fiscal Year on Sept. 30, 2020,” NMED Public Information Officer Maddy Hayden told me. “Additionally, we are just now entering into our heaviest sampling season as monsoon season begins and we collect stormwater runoff samples. We have not missed collection of any stormwater samples.”

Among the activities that were paused were a major project to pull water contaminated with chromium – a toxic, carcinogenic heavy metal – from the ground via a series of wells, treat it and inject it back into the ground in a different location.

This March 2016 photo provided by Los Alamos National Laboratory shows an angled injection well … [+]

ASSOCIATED PRESS

The chromium is the result not of nuclear weapons production, but instead of wastewater from a non-nuclear power plant that was dumped in a canyon north of TA-54 along the San Ildefonso Pueblo boundary decades ago.

N3B says it began resuming its routine groundwater monitoring again on June 8, and its chromium remediation work started to ramp up again on July 6. The goal of the so-called “chromium plume interim measure” is to hold the contamination within the LANL boundary until a permanent solution can be implemented.

“Groundwater conditions unlikely changes significantly during a 3-month shut down given that groundwater moves very slowly at depth,” NMED’s Hayden said.

But according to Joni Arends, co-founder and executive director of Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety, “there are questions about whether LANL established water levels at the time the system was shutdown and at the restart that is going on now.”

Arends says she’s also concerned that getting surface water monitoring back up and running will be a slow process.

“The monsoons began this week, so stormwater is running through the canyons to the Rio Grande.”

N3B clarified that some surface water monitoring, which is done with surveillance cameras trained on the canyons, was able to continue while all other field monitoring was shut down.

“Given LANL’s history it’s imperative that monitoring be robustly resumed,” Jay Coghlan, Executive Director of Nuclear Watch New Mexico, said in an email. “This is after all the Lab that use to claim that groundwater contamination was impossible… Now we know of heavy chromium and high explosives groundwater contamination which are a harbinger for more contaminants to come.”

In 1980, the Department of Energy published a report claiming there was no route for contaminated water from the Labs to reach the aquifer. By 2005, the DOE had reversed that stance completely, saying that contamination could be an ongoing problem for decades or even centuries to come.