If nuclear weapons are ever eliminated, it will be the result of actions big and small at every communal level, from international leaders to civil society.

Arms Control Association | December 2022 armscontrol.org

The Reverend John C. Wester occupies a unique role in this continuum as the Roman Catholic archbishop of Santa Fe, whose archdiocese is home to the Los Alamos and Sandia national nuclear laboratories and site of the first Manhattan Project nuclear tests. In January, Wester issued a pastoral letter, “Living in the Light of Christ’s Peace: A Conversation Toward Nuclear Disarmament,” which called for the abolition of nuclear weapons and declared that the archdiocese “must be part of a strong peace initiative.” He had a compelling basis for action: In 2021, Pope Francis shifted the church’s position from accepting deterrence as a legitimate rationale for nuclear weapons to decrying the possession of nuclear weapons as “immoral.” Even with the pope’s admonition, however, Wester is finding his peace initiative slow going. He discussed his efforts with Carol Giacomo, editor of Arms Control Today. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

ARMS CONTROL TODAY: You often tell the story of visiting Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 2017. It almost seems like an epiphany. How did that trip and other forces, including serving as the top Roman Catholic Church official in Santa Fe, home to Los Alamos and Sandia, propel you to take on the mission of eliminating nuclear weapons?

Archbishop John C. Wester: Until I came here to Santa Fe, I was pretty much like I believe most people are, lulled into a false sense of complacency.

I did not think much of nuclear weapons, to be honest. I do remember vividly 60 years ago during the Cuban missile crisis, but going to Japan and going to Hiroshima and Nagasaki and seeing the children, that was what really hit me most. I saw the display in the museum there, the audio and video displays and all the pictures. They had this one of the children rushing to the window to see the bright light that was detonated above their heads. That really hit me hard, it was a visceral moment, and I think it was an epiphany. It was a real sea change in my own attitude and my own consciousness of nuclear weapons.

ACT: How did you school yourself on nuclear issues, which can be an arcane subject?

Wester: It was very gradual. It involved taking my family members and friends to the museum in Santa Fe and looking at the Manhattan Project [displays]. Initially, there was a feeling in me of a kind of national pride, in what our country came up with, what the scientists and all did. Then immediately I felt, wait a minute, I’m looking at what we created and developed and manufactured and sent out to Japan. These are the very bombs I’m looking at that killed those children. So, the disconnect and the sharp contrast was so real.

As a man of faith—I believe in God, obviously—I really believe it was providential. I was asked to give a talk at our state capitol in Santa Fe on peace and nuclear disarmament, and I gave the talk. To be honest, at that time, these were words to me, and I didn’t really understand a lot of them yet. Then I met this gentleman, who went to the talk, and he’s become a very dear friend of mine now, Jay Coghlan, the head of Nuclear Watch New Mexico. He saw me afterwards, and he asked me questions. My first thought was, “Oh gosh, here’s one of these radicals.” He challenged me to be more upfront about this subject and not just to give one talk but to get into it.

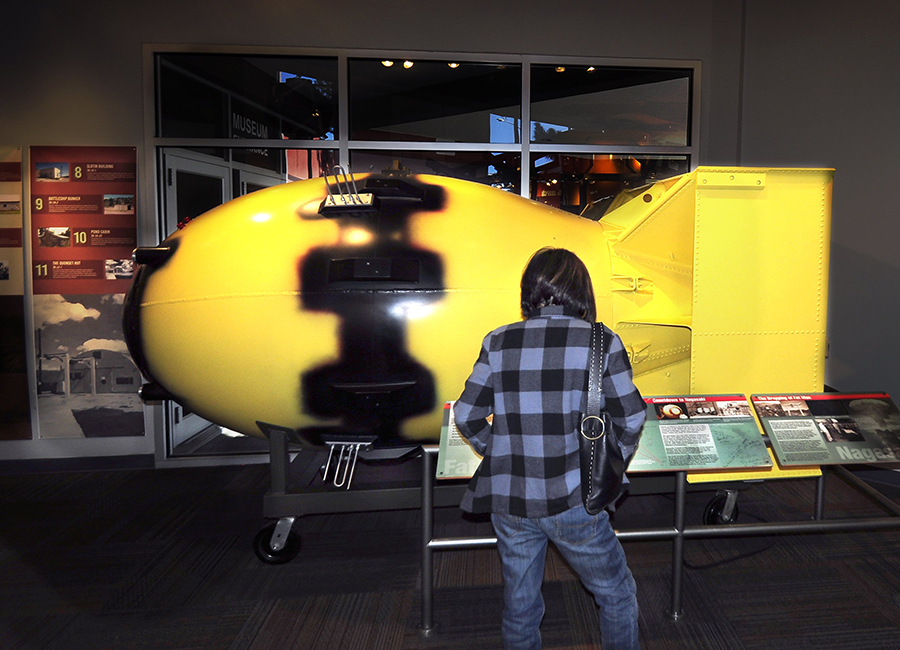

A tourist at the Bradbury Science Museum in Los Alamos, New Mexico, examines a full-size replica of the ‘Fat Man’ atomic bomb that was dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, on August 9, 1945. The museum is operated by the U.S. Department of Energy and the Los Alamos National Lab, which was established in 1943 as part of the Manhattan Project, the nation’s top secret program to develop and build the atomic bomb. The lab remains central to the U.S. nuclear program. (Photo by Robert Alexander/Getty Images)

One thing led to another, and we ended up writing a pastoral letter. I thought this is exactly what I should do as the archbishop of Santa Fe, where all these nuclear weapons programs started. Santa Fe has to have a place at the table discussing those issues. Then I started reading up, including some things that are in favor of dropping the bomb in World War II, just so I can hear more from the other side. I don’t want to be myopic on it. I’m on a steep learning curve, and I’m doing my best to get it because my whole intent is to keep the conversation going further. We have to keep talking about this until one day we can really rid the world of nuclear weapons.

ACT: Pope Francis has made disarmament a major focus, declaring that possessing nuclear weapons is “immoral.” What do you see as the faith basis for arguing for an end to nuclear weapons?

Wester: This is an extremely important point. I believe it’s an ethical principle for all human beings, regardless of their faith or if they have no faith, that Pope Francis boldly and courageously, I would say, declared that even possessing nuclear weapons is immoral. To me that moved the moral needle like crazy. In 1983 the bishops of the United States said it was okay to have nuclear weapons for deterrence, and that seemed plausible to me. But then Pope Francis says no, you can’t even possess them, what you’re doing just having them sit there is immoral.

I think that really was a wake-up call. I have to admit that it’s a good thing when the pope says it because it sure makes it easier for me because you do get interesting letters when you make a bold statement [like that]. Indeed, the pope is right on target because nuclear weapons are immoral; and considering their potential lethalness, they could destroy all of us and the planet and civilization. If anyone still survived the nuclear winter, it would send us all back to the ice age. We’d all be in caves and writing on the walls, and everything would have to be reinvented, you know, the alphabet and penicillin and you name it. I’m learning quickly that people don’t want to talk about it.

ACT: You recently gave a speech in which you noted that the U.S. Catholic Church and the media have ignored the pope’s call. If the pope made such an issue of nuclear weapons, why aren’t all clergy speaking out? If you can’t get the Catholic clergy to do it, how can you expect to rally others?

Wester: It’s a very good question, but it’s a complicated one. Part of it has to do with the polarization in our world and our politics and in our church, and part of it has to do with a more conservative approach, even to things like defenses and the whole nuclear armament question. I think it’s also tied to a new point that the pope has made that nuclear weapons are immoral. A lot of people that I’m conversing with, and I welcome all angles, really do believe that we need these nuclear arms for deterrence. They think that this is the right way to go. I would say, unfortunately, they don’t understand.

As [U.S. Secretary of Defense] Robert McNamara said many decades ago, the only reason we didn’t have a problem in the Cuban missile crisis was because of luck. We’ve been lucky. We’ve had miscues, such as Soviet submarine officers who decided not to fire their nuclear weapons. There have been bombs dropped, even here in Albuquerque, that did not detonate because one last little low-voltage switch didn’t turn on and luckily nothing detonated. How long is our luck going to last? Anybody who gambles for a living will tell you it never lasts forever. But this is something that people, either because they don’t want to or because they’re afraid to think of it, just don’t want to deal with. Yet, we have to do it because if we don’t do it now, it’s going to be too late; and once it’s too late, it truly is too late.

ACT: What feedback have you gotten as you advocate eliminating nuclear weapons?

Wester: The response I’ve gotten, including from the archdiocese and the church in general, has been—how would I characterize it? If you’re a teacher, grading on the A-thru-F scale, I’d put it at a C-minus. The response has been polite. Some people, very few, have said, “Wow, we’re so glad you did this, it’s so important.” The people you’d expect [with disarmament organizations] have been very favorable, but in the general population, I’d say it has been polite but very unengaged, not wanting to talk about it. My sense is that they’re hoping the issue will just go away. That’s one thing we’re doing our very best not to let happen. We’ve translated the pastoral letter into Japanese and Korean and Spanish. We’ve just ordered 1,000 more copies in Spanish, so we’re doing our very best to get the word out to keep this conversation going.

But the response has been lackluster. I haven’t gotten a lot of hate mail. Maybe that’s because, deep down, most people do understand that nuclear weapons are not a good thing. I’m trying to read that. Maybe deep down, they know we do have to do something about it but would just as soon someone else do it. I think, too, with the Ukraine war and with [Russian] President [Vladimir] Putin rattling his nuclear saber, that scares people. India-Pakistan, China-Taiwan, Iran, all of these geopolitical issues scare people. They’re probably feeling the best offense is a good defense so let’s keep building these plutonium pit cores [for nuclear weapons] and let’s keep doing what we’re doing. What we’re doing is really pursuing a second arms race that’s probably more dangerous than the first.

ACT: Have you met with executives at the labs at Los Alamos and Sandia or with defense industry CEOs?

Workers conduct an analysis of plutonium at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico where plutonium pits for nuclear weapons are manufactured. (Photo courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory)

Wester: Yes. We are going to. We had quite a few date possibilities this last summer. I was going to meet with scientists in the Los Alamos labs, and we’re still going to do it, we just could not come up with a date, I suppose because of the vacations and all. So, I want to have that conversation. I have gotten some responses from some engineers and scientists at Sandia and Los Alamos that have been positive. They’ve said they agree with the pastoral letter. They read the summary of it at least, and they do agree with its ultimate desire to rid the world of nuclear arms. But my sense is that they think that we have quite a few steps to take before we get there. It’s hedging their bets maybe. We’ve already waited too long. There are 13,000 weapons in the world today, with more being produced. Several countries are modernizing their weapons, including with hypersonic delivery systems, and all this portends badly for the future.

ACT: Presumably, some people are worried about losing jobs if the nuclear industry goes away. You have suggested that if nuclear weapons are eliminated, the scientists and their skills can be used for other things such as verification work and environmental cleanup. Do people consider that argument credible?

Wester: The feedback has been mixed. I think it’s more one of disbelief, like, prove it, show me. We’re working on that, trying to get more statistics. I think there are two points there, though, that really are compelling. One is that there’s going to be about $9.4 billion spent by the U.S. Department of Energy in New Mexico this fiscal year for nuclear weapons development, most of it for Los Alamos and plutonium pit core production, and also for the Sandia labs for nuclear weapons life extension programs. I think it’s $8.5 billion. So, that’s 10 percent more than the state of New Mexico’s entire operating budget. People see those numbers and they go, “New Mexico is benefiting from all this money,” but in fact New Mexico is not benefiting from all this money. There are some who are, and obviously Los Alamos is one of the wealthiest areas of the United States. But the money does not really trickle down to the average citizen in New Mexico. It’s kind of a red herring to think that all this money is going to help. It doesn’t.

Number two, the labs are already doing other things besides developing and building nuclear arms. They were at work helping with the COVID-19 crisis. They also do work in the medical field and on climate control questions, and if we really do have verifiable, multilateral nuclear disarmament, we’re going to need very clean and well-developed technology to do what [President Ronald] Reagan said, trust and verify. That’s going to be a huge industry. I don’t deny that whenever there’s a switch—when the Industrial Revolution came along, or when technology and computers came along—obviously there are going to be instances of people losing a particular job. But in the main, I believe there’ll be far more jobs available because of this. Plus, this is going to be a gradual thing. We’re not going to unilaterally disarm tomorrow morning. So, I think the job question can definitely be answered clearly and, I think, satisfactorily.

ACT: Is there anybody in the New Mexico congressional delegation who’s been particularly supportive?

Wester: Yes. I think Representative Melanie Stansbury has been supportive, and I’m very grateful to her. But our delegation pretty much is backing up the nuclear weapons industry here in New Mexico, and this is going to be a tough nut to crack. But we’re going to do our very best to do so because we’ve got to really make our case with them, and we have to make the case at the grassroots level. We’re trying to develop a grassroots here to get our archdiocesan and parish peace and justice commissions to be more conversant on the pastoral letter and on this issue so they can start writing letters. Politicians want to know where the votes are, and if we can show them that we’ve got the votes, that’s going to make a big difference.

ACT: In a June public statement, you asked what the United States was afraid of when it refused to even attend a meeting of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. Later, you accused nuclear-weapon states of having no intention to honor their pledge to eliminate nuclear weapons. Have you gotten any pushback from federal officials on such comments?

Wester: Not to my knowledge. I know when I came out with my [state capitol speech] a couple years ago, I got pushback from the local paper, the Albuquerque Journal, which is a conservative-biased paper. They refuted my speech, and to their credit, they published a letter to the editor that we wrote back as a counterrefutation. I’m a pretty small voice in this whole question. I don’t think people really hear my voice. But maybe if I keep speaking, I’ll become annoying enough. It’s going to take real leadership to do what we’re asking, for the United States to take the lead and work with the other nuclear parties to say, “Look, we’ve got to do something about this.” In my opinion, we also have to come to an agreement that we will not have any first-strike plans in our nuclear posture review. That alone would be a very important first step.

Right now, everybody’s too afraid to make the first move, and I think the United States has to do that. I think President Joe Biden and his administration are handling the Ukraine war tragedy very well and they’re trying to tamp down any panic or possibility of miscommunication [prompted by Putin’s nuclear threats]. I think they’re doing as best they can, given the circumstances. They’ve taken real leadership on this, and the way I see the geopolitical landscape right now, I think the United States is the one to make that first step [on nuclear policy as well].

ACT: What did you think of the administration’s new nuclear policy review, which did not include a no-first-use nuclear strike component?

Wester: I’m a neophyte in many ways on this, but from my vantage point, I found the Nuclear Posture Review that came out recently very disappointing. It’s going in exactly the wrong directions and not showing the necessary leadership. It’s frustrating that a lot of times, politicians will say things as they go up the ladder, but then when they get to a position where they really can do something, they pull back. They’re privy to information I don’t have, obviously, but it seems to be quite logical that having these nuclear arms is just untenable and we’ve got to do something about it and we’ve got to start taking the first step.

We’re not asking President Biden or President Putin or [Chinese] President Xi Jinping to unilaterally disarm. We’re asking them to begin. Why can’t we go back to those days when we went from, like, 60,000 nuclear weapons down to what we have now, 13,000? That was quite a significant reduction in nuclear armaments. It seems to me that we could take the leadership and start that diplomacy going again. But for some reason, there just does not seem to be the will at those higher levels that you speak of.

ACT: As you mentioned earlier, we are in a different political environment, and there’s a real turn, certainly in this country, toward grievance and vitriol. That’s a pretty tough environment in which to make policy that breaks the mold.

Wester: You’re right, and it’s absolutely irresponsible, for example, for the U.S. president to say [as President Donald Trump said to North Korean leader Kim Jung Un], “If you do this, you’re going to see more hellfire from heaven than you’ve ever seen before.” We’re just trying to get a political leader to move the needle back to the middle where he will be diplomatic and careful and prudent of what he says.

ACT: Are there any concluding points you want to make?

Wester: There’s one thing that really speaks to me, and that is, as I am doing this, I do get the impression that a lot of people look at me and say, “Oh well, archbishop, aren’t you a nice man, why don’t you just go back to your sacristy and say your prayers and don’t stick your nose where it doesn’t belong.” I have a feeling that what they’re saying to me is, “You’re just being naive, you really don’t understand what we’re dealing with, we’re the scientists, we’re the politicians, we’re the ones who know what we’re talking about.” I would say back to them, who really is it that’s being naive? If they look at all the years now that we’ve had nuclear weapons, as I’ve said earlier, and as McNamara, [President Dwight] Eisenhower, Reagan have said, really, it’s only by luck that we haven’t destroyed the planet yet.

It’s far more naive to think that we can continue the way that we’re going, building up our nuclear arms, and to think that luck is going to save the day. To me, that’s the epitome of naiveté. What we need to do is roll up our sleeves and start talking seriously about the danger our planet Earth is in. You talk about climate change; this to me is the number one issue of climate change. You talk about the sanctity of human life; this to me is the number one issue of human life, because these bombs would destroy all of human life and all of any living, sentient beings. So, I’m waiting for the day for somebody to come up and just say it, you know, archbishop, you’re a bit naive. Oh? Because I think you’re naive.