The legendary civil rights activist pushed to ban nuclear weapons, end the Vietnam War, and lift people out of poverty through labor unions and access to healthcare.

“It cannot be disputed that a full-scale nuclear war would be utterly catastrophic,” he told Ebony magazine in an interview. “The principal objective of all nations must be the total abolition of war.”

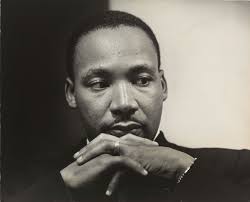

During his lifetime, King’s views often made him unpopular and heralded harsh criticism. At the time of his assassination in 1968, a Harris poll revealed a low approval rating of only about 25 percent among white Americans and 52 percent among Black Americans. But in the decades after he was killed, more Americans came to recognize the enormity of King’s contributions. Communities across the country began to name streets and landmarks after him, and soon a push began to establish a federal holiday in his birth month of January.In 1983, over objections from Southern lawmakers, President Ronald Reagan finally signed a bill creating the holiday into law and the first celebrations of Martin Luther King, Jr. Day took place in January 1986—although it would take another decade for states such as Arizona and South Carolina to follow suit.

King’s work continues to influence and inspire activism—particularly in the realm of environmental justice, as studies indicate that climate change disproportionately harms marginalized communities. Here are the many layers of King’s work that the U.S. honors on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day.

He advocated against the use of nuclear weapons

King was adamant that peace was inextricably linked to civil rights. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, major powers like the United States and the U.S.S.R. were aggressively developing and testing nuclear weapons, and several times crept to the brink of warfare that threatened to annihilate the world.

King made clear the connection between the Black freedom struggle and the need for nuclear disarmament, writes nuclear studies and African American history expert Vincent Intondi in the book African Americans Against the Bomb: Nuclear Weapons, Colonialism, and the Black Freedom Movement. King argued that it would be “rather absurd” to integrate schools and lunch counters but not be concerned with world peace and survival.

King spoke out about nuclear warfare as early as 1957, when he signed onto a full-page advertisement in The New York Times that called for all nations to suspend nuclear tests immediately. When asked about his stance later that same year, King tied the weapons to the whole of war, and argued that they should be banned everywhere.

“It cannot be disputed that a full-scale nuclear war would be utterly catastrophic,” he told Ebony magazine in an interview. “The principal objective of all nations must be the total abolition of war.”

As part of King’s advocacy for peace and nuclear disarmament, he condemned the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki the U.S. government had carried out more than a decade earlier to effectively end World War II. Today, Hiroshima is one of the only cities outside North America to celebrate Martin Luther King Day.

King also used the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962—a 13-day stretch in which the U.S. and Soviet Union stood on the brink of nuclear war over the discovery of Soviet missiles in Cuba—as an opportunity to connect nuclear disarmament to racial and economic justice. King called for the U.S. government to instead turn its attention and funds to education, Medicare, and civil rights, Intondi writes. He then voiced his support for a nuclear test ban treaty, which was signed by President John F. Kennedy in 1963.

He was outspoken against the Vietnam War

King often linked nuclear disarmament with the Vietnam War as it escalated in the 1960s.

King was against the war but initially worried that making his stance public would derail his work to pass the Civil Rights Act and impair his relationship with President Lyndon B. Johnson, according to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University.

But in 1965, the year the first U.S. ground troops were sent to Vietnam, King issued his first public statement, asserting the war was “accomplishing nothing” and calling for a peace treaty.

He tempered his criticism for the next two years to avoid diminishing the impact of his civil rights work, but by 1967, King was active in the anti-war sphere again, attending a march in Chicago before he went on to make his most notable speech on the matter a few days later on April 4.

On that day at the Riverside Church in New York City, King denounced the war for deepening the problems of Black Americans and people living in poverty. He condemned the “madness” of Vietnam as a “symptom of a far deeper malady” that put the U.S. at odds with the aspirations for social justice throughout the world. Just 11 days later, King led 125,000 demonstrators on an anti-war march to the United Nations headquarters in New York as one of the largest peace demonstrations in history.

During the last year of his life, King continued his anti-war work by encouraging grassroots peace activism. On March 31, 1968, five days before he died, King denounced the Vietnam War in his final Sunday sermon at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., saying that it was “one of the most unjust wars that has ever been fought in the history of the world.”

King did not live to see the war end. U.S. troops officially pulled out of Vietnam in April 1975.

He championed union representation and worker’s rights

King’s passion for union representation and workers’ rights is also an important part of his legacy. Much as he had done with his anti-war speeches, King often tied workers’ rights to the civil rights movement.

“I had also learned that the inseparable twin of racial injustice was economic injustice,” King said in a 1958 speech in New York. “Although I came from a home of economic security and relative comfort, I could never get out of my mind the economic insecurity of many of my playmates and the tragic poverty of those living around me.”

In a 1959 interview with Challenge magazine, King acknowledged that labor unions had historically left out Black Americans, but also could be a key to economic justice. He called for Black Americans to organize their economic and political power in the form of labor unions, and he championed ideas in the labor movement, including better working conditions, adequate housing, guaranteed annual income, and access to healthcare.

For years, King continued to call for economic justice, notably at the August 28, 1963, March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Before a crowd of 250,000 people, he delivered the legendary “I Have A Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, where he called for an end to poverty, especially targeted poverty and discrimination against Black Americans.

One of King’s last actions before his assassination was in support of the labor movement. King’s final days were spent supporting a group of Black sanitation workers striking in Memphis, Tennessee.

After two workers had been crushed to death by a malfunctioning truck, 1,300 Black workers went on strike for 11 days, seeking an end to a long pattern of neglect and abuse from their management. The strike would’ve ended after the City Council voted to recognize their newly formed union, but the Memphis mayor rejected the vote. King traveled to Memphis to lead a protest march and, on April 3, he spoke to the striking sanitation workers.

“We’ve got to give ourselves to this struggle until the end,” King said. “Nothing would be more tragic than to stop at this point in Memphis. We’ve got to see it through.”

King was gunned down by an assassin on the balcony of his Memphis hotel the next day. On April 16, the sanitation workers’ union was finally recognized and a better wage was promised—the first of many examples of how King’s legacy would continue to reverberate in the work of those whom he inspired.

He’s inspiring a new generation of environmental activists

Although King’s last act supporting the Black sanitation workers in Memphis was not explicitly an act of environmental justice, it has inspired a generation of activists. The working conditions the sanitation workers had endured were polluted and hazardous—much like the conditions many Black Americans endured in their communities and jobs at the time.

Modern environmental activists have drawn on King’s message: Much as segregation and discrimination were inseparable from poverty, they point out that poor communities of color disproportionately face environmental hazards such as pollution. They also bear the brunt of the harmful effects of climate change, including extreme weather events.

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits discrimination in the use of federal funds, even gave marginalized people a means to address racial discrimination in environmental matters. As the environmental justice movement grew, King’s work also inspired the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Endangered Species Act.

His advocacy for people of color to have a voice and power has inspired many communities impacted most by climate change to speak up—and take action. Now, the holiday honoring King is typically observed as a national day of service. Organizations and individuals alike volunteer for their communities, often cleaning up roads or river banks in the name of a man who many believe would be on the forefront of the climate fight if he were still alive today.