“The agency has said little overall about its plans, despite the potential hazards, said Cindy Weehler, who co-chairs the watchdog group 285 ALL.”

A panel of state lawmakers expressed concerns Friday about plans to truck plutonium shipments through New Mexico, including Santa Fe’s southern edge, and will send letters to state and federal officials asking for more information on the transports.

Two opponents of the shipments — a Santa Fe County commissioner and a local activist — presented the Department of Energy’s basic plan to the Legislature’s Radioactive and Hazardous Materials Committee, provoking a mixture of surprise and curiosity from members.

Several lawmakers agreed transporting plutonium is more hazardous because it is far more radioactive than the transuranic waste — contaminated gloves, equipment, clothing, soil and other materials — that Los Alamos National Laboratory now ships to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, an underground disposal site near Carlsbad.

County Commissioner Anna Hansen told the committee the shipments would travel through a dozen states and cover 3,000 miles — and they would go through Santa Fe twice in different forms.

“This is truly quite concerning,” said state Sen. Nancy Rodriguez, D-Santa Fe. “It’s obvious we need a plan — we need safety planning here. A better strategy for this whole transportation issue.”

The Energy Department issued a notice of intent in December to begin the process for an environmental impact statement as one of the first steps toward diluting and disposing of plutonium left over from the Cold War.

The notice hints “downblending” the plutonium would be necessary to reduce radioactivity enough for the waste to be accepted at WIPP, which only takes low-intensity nuclear waste.

The agency has said little overall about its plans, despite the potential hazards, said Cindy Weehler, who co-chairs the watchdog group 285 ALL.

Most of the information has come from the National Academy of Sciences, which describes how surplus plutonium would be transported, reconstituted and disposed of at WIPP in its 2020 analysis, she said.

The agency’s lack of transparency about the transports could imperil communities more because they’ll be unaware and unprepared, Weehler said.

“We’ve learned that fire departments aren’t even aware of most of the new risks they’ll be handling,” Weehler said. “The DOE needs to make this public. It’s becoming incumbent upon us citizens to make this public.”

State Sen. Jeff Steinborn, D-Las Cruces, agreed that the agency should be more forthcoming and suggested the committee send letters to the Governor’s Office and federal nuclear managers asking that they dig into the matter and get answers.Committee members voted in favor of the letters.

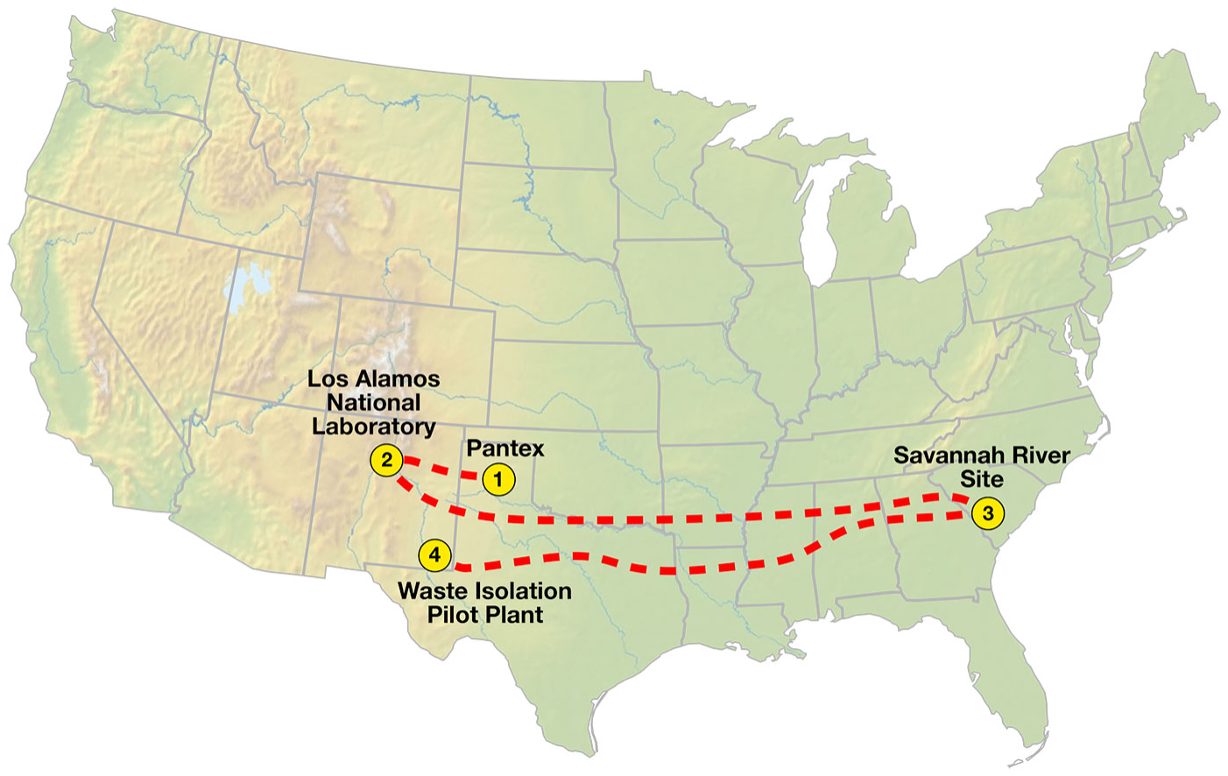

A big concern would be the 26 metric tons of cast-off plutonium bomb cores, or pits, that are being kept at the Pantex Plant in Amarillo, Texas, Hansen said.

This plutonium would be sent to Los Alamos, where it would be turned into an oxide powder, and then the powder would be shipped to the Savannah River Site in South Carolina, where it would be further diluted before returning to New Mexico for storage at WIPP, according to the academy’s report.

That would mean a more hazardous substance would be transported twice on N.M. 599 and U.S. 84/285 — when the plutonium comes in from Pantex and when the lab ships the powder, Hansen said.

“This a dangerous way to be transporting nuclear weapons-grade plutonium,” Hansen said.

N.M. 599 was designed so nuclear materials being trucked to and from the lab would bypass the heart of Santa Fe.

But Weehler contends a truck accident could still endanger some neighborhoods, especially one carrying the plutonium powder, which won’t be in heavy duty containers and is more likely to be released. The powder is toxic to breathe — the fine grains can embed in the lungs, causing respiratory problems — and can contaminate soil so extensively it’s impossible to purge, she said.

Steinborn said the committee by law is charged with overseeing the public safety and welfare of residents, and to do that it requires agencies to be cooperative and transparent.

“These issues do represent fundamental exposure to citizens of the state,” Steinborn said. “And citizens have a right to know.”