Are the stars finally aligning for Washington and Moscow to extend the New START treaty?

ARTICLE & ANALYSIS BY: HANS KRISTENSEN & MATT KORDA | forbes.com

Nuclear arms control is reportedly on the agenda for a rush-meeting between Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov and US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo today. Over the past weeks, Russia had softened its preconditions for extending the New START Treaty––the only strategic arms control agreement still in place between the two nuclear superpower––while

President Donald Trump last week said that he had spoken with President Vladimir Putin and “we are – he very much wants to, and so do we, work out a treaty of some kind on nuclear weapons…”

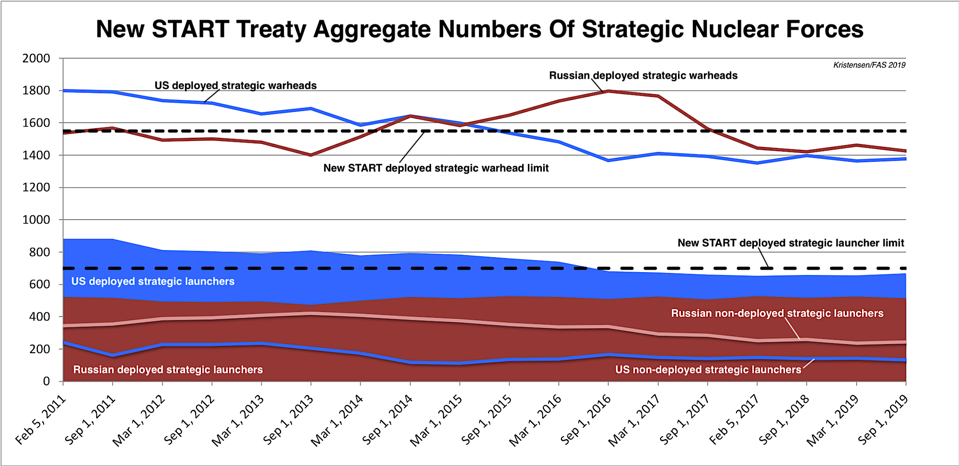

The New START treaty limits US and Russian deployed strategic nuclear forces, and additionally facilitates inspections and exchanges of information on the status and movements of their intercontinental ballistic missiles and heavy bombers. Signed in 2010, the treaty expires in February 2021 but can be extended for another five years.There is nothing other than personalities and bad advice that is preventing Moscow and Washington from extending New START. Retaining the treaty is clearly in the interest of both countries, particularly as other arms control agreements have been abandoned and military tensions are steadily increasing.

Yet, over the past years, US and Russian officials have raised a host of issues that they said prevented extension in the treaty’s current form. President Trump has called New START a “bad deal,” even though it isn’t (the US currently has 155 more deployed strategic launchers than Russia, and the treaty has forced Russia to lower the warhead loading on some of its missiles). Similarly, President Putin has complained that Russia can’t verify that denuclearized US launchers can’t be returned to a nuclear role again, even though the treaty doesn’t require irreversibility and the launchers have been converted in accordance with procedures that Russia agreed to when it signed the treaty.

Last week, however, in a rare display of constructiveness, Vladimir Putin suddenly offered to immediately extend the New START treaty “without any preconditions.” And Trump added: “We are looking at doing a new agreement with Russia, and we’re looking at doing a new agreement with China. And maybe the three of us will do it together…We may do it with Russia first and then go to China, or we may do it altogether…”

This should, in theory, put the matter to bed. New START extension is widely supported across the country, even among Trump voters; in fact, it’s one of the very few bipartisan issues still remaining in Congress. Senior military leaders, such as the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the commander of Air Force Global Strike Command, have declared their full support for the treaty. It should a no-brainer.

If the treaty is allowed to expire, there will be no constraints on US and Russian strategic nuclear forces for the first time since the 1970s. The point of extending New START is not about arms control for the sake of arms control, but rather to retain limits and transparency on the most dangerous nuclear weapons at a crucial point when East-West relations are strained––and could potentially get worse. This is a matter of national security.

Without the treaty, US and Russian nuclear posture planning will be thrown into an era of unpredictability, with grave consequences for both strategic stability and the expensive nuclear modernization programs that both countries currently have underway. Those programs are based on the assumption that both countries will remain at New START force levels; without the limits of the treaty, both sides would have to reassess their programs in order to accommodate unconstrained postures, likely resulting in significant increases to each country’s nuclear arsenal.

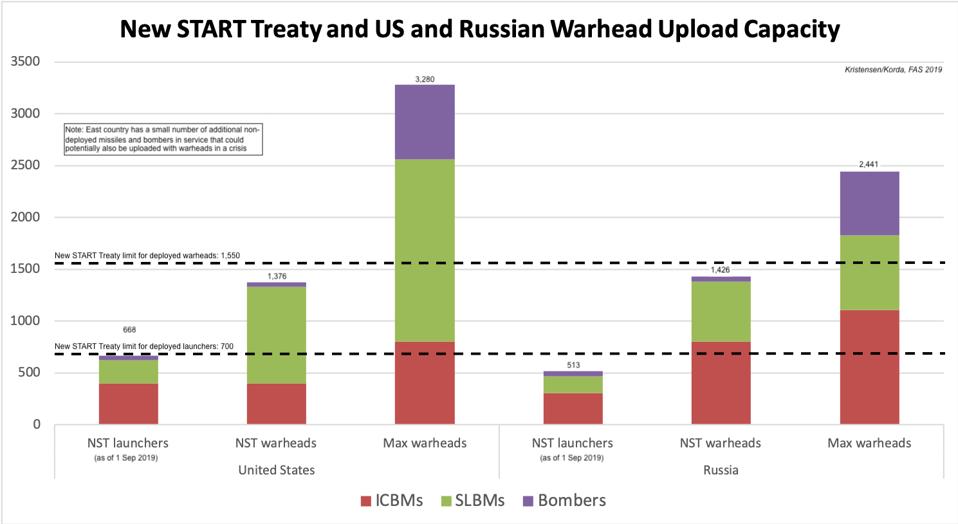

Without the constraints of New START, Russia could quickly upload hundreds of warheads onto its deployed ballistic missiles and bombers. As Rose Gottemoeller, former Deputy Secretary of NATO, testified last week, “without deploying a single additional missile, they could go from 1,550 deployed warheads possibly to as many as 2,550 deployed warheads.”

The United States also has a significant warhead upload capability and could, if New START fell away, increase its deployed strategic warheads from 1,550 to more than 3,500 warheads. Most of those would be on Trident submarines, which have the largest upload capacity in the US arsenal. It is the capacity of the Trident force and the significantly greater number of total deployed launchers – 155 by the latest official count – that give the United States this edge.

So New START is by no means a “bad deal” for the United States. Nor can Russia “outrun” the United States. Doing so would require production and deployment of significant numbers of new launchers. Only a few years ago, the Pentagon and the Intelligence Community concluded that even a Russian breakout from New START with deployment of significantly more warheads would not give Russia a military advantage.

Yet the significant upload capacity in both US and Russia strategic arsenals––as well as recent warnings by some that Russia can break out of New START and outrun the United States––illustrate the destabilizing effect that large inventories of unaccounted warheads can have. It is a reminder of what would happen if New START fell away: deepening distrust and worst-case scenario planning, resulting in increased strategic competition and nuclear tensions.

Additionally, if the treaty expired, the United States would instantly lose a critical and irreplaceable window into Russia’s nuclear complex. Under New START, the United States is notified every time a Russian missile is deployed, every time a missile or bomber moves between bases, and every time a new missile is produced. Nearly 20,000 such notifications have been exchanged since New START entered into force in February 2011. Given that Russia’s missiles are significantly more mobile than their American counterparts, receiving an immediate alert whenever a missile is on the move benefits the United States significantly more than it does Russia. Additionally, the United States is also allowed to conduct 18 on-site inspections of Russian missile bases every year, in order to confirm that Russia isn’t cheating. Russia is allowed the same number of inspections of US facilities. As senior military leaders have repeated stated, these are incredibly valuable sources of intelligence that simply cannot be replicated by national technical means. Why would we willingly give them up?

Rare critics of New START argue that Russia’s suite of exotic new nuclear systems, unveiled in March 2018, might not easily fit into the treaty’s counting rules. However, these concerns were recently put to rest in late November, when senior Russian arms control officials publicly declared that two of the incoming systems – the Sarmat intercontinental ballistic missile and the Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle – would be able to “enter the treaty very smoothly.” The first of these, the Avangard, was shown to US inspectors in an “exhibit” as required under the treaty. The other two systems of note – a nuclear torpedo and the nuclear-powered cruise missile that reportedly exploded during a test in August – are not scheduled to enter service until at least 2027, a year after New START would expire if Trump decided to extend it past 2021. So these systems are essentially irrelevant when considering whether to extend the treaty until 2026 and are, in any case, not expected to be deployed in significant numbers.

And then there’s the issue of China. The Trump administration has argued that New START ignores China and is therefore inadequate in today’s security environment. China was initially raised as part of the Trump administration’s decision to withdraw from the INF treaty but has since been imported into arguments against extending New START as well. While China has a large inventory of intermediate-range missiles, it only has about 128 deployed strategic missiles that would be covered by the New START treaty limits; in sharp contrast, the United States has 640 deployed strategic missiles counted by the treaty.

Moreover, none of China’s missiles are thought to be loaded with warheads in peacetime and would therefore count as 0 deployed warheads under New START. The entire Chinese arsenal is thought to include about 300 warheads, a fraction of the 4,000-4,500 in the US and Russian arsenals (not counting thousands more retired––but still intact––warheads awaiting dismantlement). And while China is indeed increasing its arsenal, it’s not nearly by as much as some claim. Chinese officials have therefore consistently stated that there is no basis for China to join New START; there is no strategic balance.

Therefore, killing New START because it doesn’t include China is a flawed strategy. It would do nothing to address the United States’ security concerns about Chinese nuclear forces, but instead remove its ability to keep a lid on Russia’s much larger nuclear arsenal. Moreover, if the nuclear constraints on both Russia and the United States suddenly disappeared, China might well decide that it needs to dramatically increase its stockpile in order to adjust to the greater nuclear threat. This would further exacerbate a post-New START nuclear crisis.

Having said that, the instinct to include China in arms control and disarmament negotiations is a good one, and such negotiations should eventually be pursued. It is also important to work to place limits on shorter-range nuclear weapons. If China was persuaded to join a future arms control agreement, Russia would almost certainly insist that France and Britain should be constrained as well. It will require many years of consistent and focused diplomatic work to achieve this, and New START––with its very tight extension deadline––is clearly the wrong forum to do so. Those who insist that China must be brought in now have not presented any ideas about what the United States would offer China in return.

It’s no coincidence that those looking for an excuse to kill the New START treaty have settled on the China angle; forcing China to join New START as a precondition for its extension is a poison pill that will only end with the treaty’s death.

Not only is New START treaty extension a no-brainer, it’s also one of the lowest-hanging pieces of fruit available. It doesn’t require Congressional review or consent; it takes nothing more than a presidential stroke of a pen. President Putin has offered to do so; it’s now up to President Trump to do the same. Time is running out quickly.