The Department of Energy controls many ‘black projects’ that live outside of the limelight that is intrinsic to the DoD and the intel community.

BY BRETT TINGLEY | thedrive.com May 13, 2021

When it comes to discussions of government secrecy, much of the conversation tends to revolve around the Department of Defense (DOD) or the U.S. Intelligence Community (IC). After all, the U.S. military develops many of the United States’ most sensitive weapon systems used to defend America and project its power globally, and the IC gathers and analyzes sensitive information on foreign threats and external national security matters. Each year, the budget requests from the U.S. military are packed with classified and Special Access Programs, or SAPs, sporting vague code names, many of which never see the light of day. When we talk of the “black world,” most often that conversation centers around these programs and technologies suspected to be housed deep within the classified ends of the Pentagon and its various service branches.

Often left out of this conversation is the fact that there is a wholly separate cabinet-level department of the U.S. government that is arguably even more opaque in terms of secrecy and oversight than the Department of Defense. Over the last few years, allegations of secret, exotic technologies have reinvigorated claims that the DOD may be concealing scientific breakthroughs from the American public. However, if the U.S. government, or some faction within it, hypothetically came across a groundbreaking development in energy production or applied physics, a very strong case could be made that such a revolution would likely be housed deep within the Department of Energy (DOE) rather than DOD.

Laying The Atomic Groundwork

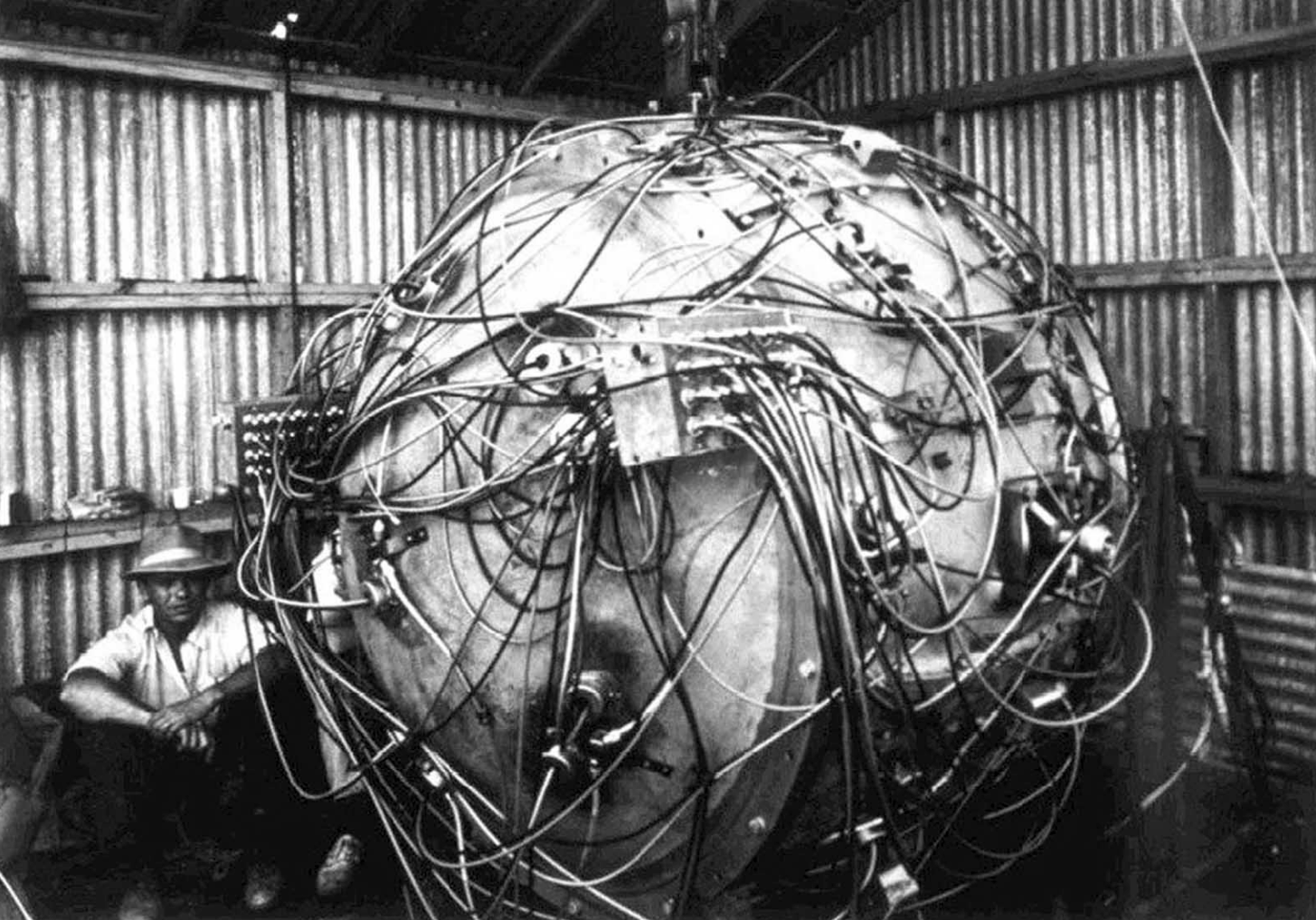

The Department of Energy was officially formed in 1977, although its roots were planted in the Atomic Energy Act of 1946. The Atomic Energy Act established the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), an agency designed to manage and control the United States’ nuclear technology under a civilian regime, rather than one overseen directly by the military itself. This is a gray area of sorts, however, as there are and have always been numerous positions at both the DOE and National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) filled by uniformed military officers. For example, NNSA’s Deputy Administrator for Naval Reactors, who also heads up the joint Navy-DOE Naval Nuclear Propulsion Program, is and has always been an admiral.

Ultimately, one of the main points of the AEC was to bring all of the United States’ nuclear technologies firmly together under one roof. From the beginning, the AEC focused almost exclusively on designing and manufacturing nuclear weapons and nuclear reactors for naval use. With the passage of the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, the AEC also began exclusively regulating the growing commercial nuclear power industry.

Like the DOE of today, AEC was focused on much more than simply the weaponization of nuclear technologies. Many atomic scientists intended nuclear explosives to be used for much more than simply weapons. As early as the 1950s, scientists at what are today Los Alamos National Laboratory and Sandia National Laboratories held classified discussions “to discuss the possibilities of using energy unleashed by nuclear explosions to produce power, dig excavations, and produce isotopes.” The AEC continued looking into these industrial uses of atomic technologies throughout the 1960s and early 1970s as part of its Plowshare Program.

Motivated in large part by the oil crisis of the early 1970s, the United States government under President Jimmy Carter passed The Department of Energy Organization Act of 1977. With that, the DOE as we know it today was formed by bringing together many different energy and science programs and administrations under one roof. This new department would oversee “long-term, high-risk research and development of energy technology, federal power marketing, energy conservation, the nuclear weapons program, energy regulatory programs, and a central energy data collection and analysis program.”

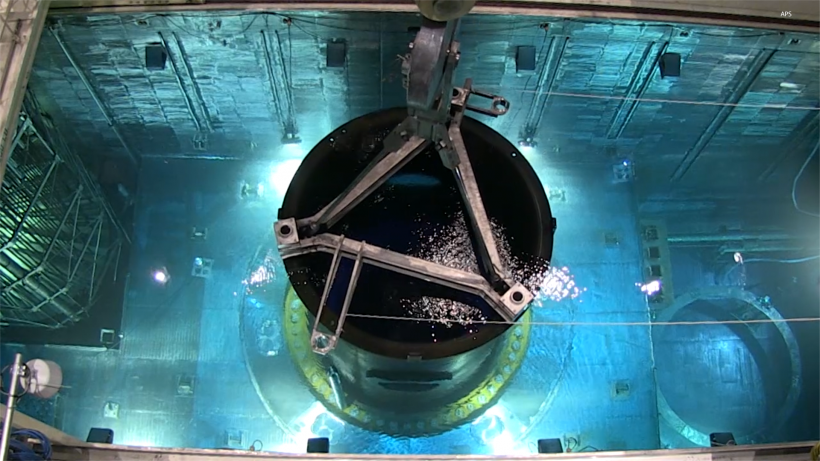

One of the main tasks of DOE today is to develop, test, and maintain the United States’ nuclear weapons stockpile. While the DOD develops, operates, and maintains the systems that deliver those nuclear weapons, the DOE is the department actually tasked with the development and acquisition of nuclear warhead technologies. DOE handles all functions not related to warhead delivery: storing and securing nuclear warheads that are not deployed onboard DOD systems, securing the materials that are used in nuclear weapons, and dismantling older nuclear weapons which have been removed from the national stockpile. To facilitate cooperation between the two, the Nuclear Weapons Council was established in 1986. This council consists of senior level officials from both the DOE and the DOD who coordinate on interagency activities related to the maintenance of the U.S. nuclear stockpile.

In addition to controlling and producing America’s nuclear power and weapons technologies, today’s DOE fosters research and innovation into clean energy solutions, energy efficiency, climate change mitigation, and alternative fuel technologies for the transportation sector. As its name implies, DOE has a hand in all of America’s short- and long-term energy needs. That’s far from all that the DOE oversees, however, as it also conducts a significant amount of secret and classified research and manufacturing.

Secrecy And Classification In The Department Of Energy

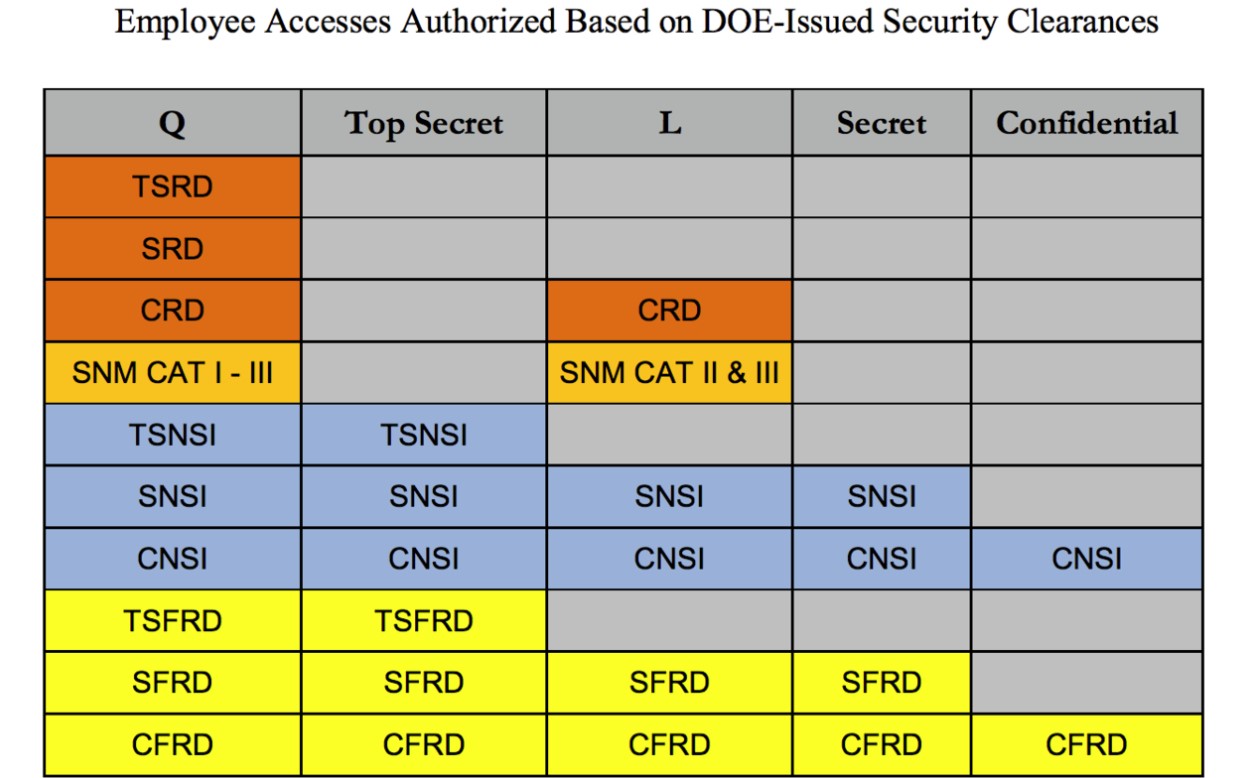

In many cases, DOE has its own classification systems and policies, some of which are even classified themselves. The highest level of these DOE security clearances is the Q clearance, equivalent to a Top Secret clearance in the DOD. That doesn’t mean that anyone with a Q clearance can access all classified information overseen by DOE. According to its Personnel Security FAQs page, “for access to some classified information, such as Sensitive Compartmented Information (SCI) or Special Access Programs (SAPS), additional requirements or special conditions may be imposed by the information owner even if the person is otherwise eligible to be granted a security clearance or access authorization.”

Groups, such as the Federation of American Scientists (FAS), through its Project on Government Secrecy, are actively pursuing further declassification of DOE records and have managed to get the DOE to declassify many records related to American nuclear technology. Despite these efforts, the DOE still remains one of the most secretive institutions of the U.S. government.

Steven Aftergood, director of FAS’s Project on Government Secrecy, told The War Zone that these extreme levels of secrecy were baked right into the DOE from the beginning, explaining:

One of the unique features of government secrecy at the Department of Energy is that it is shaped in part by law – the Atomic Energy Act – and not just by executive order. So it can be even slower and more difficult to change or to update than at some other agencies.

Not only that, DOE secrecy policy on nuclear weapons is intertwined to a great extent with the policy of the Department of Defense. When the two agencies differ on whether to declassify and disclose information, either one can veto the decision.

We’ve seen this happen repeatedly. So, for example, the size of the US nuclear arsenal was declassified most recently in 2017. We asked for the number of weapons to be updated in 2018 and 2019, and DOE was willing to do so, but the Department of Defense blocked the disclosure.

Protecting this highly sensitive information is obviously a top priority for the DOE, and for that reason, the agency operates its own independent intelligence and counterintelligence arms, which are part of its relatively extensive and uniquely equipped apparatus of security forces. The DOE’s Office of Intelligence and Counterintelligence (OICI) was founded along with the Department in 1977, and aims to “identify and mitigate threats to U.S. national security and the DOE Enterprise and inform national security decision making through scientific and technical expertise.”

The OICI answers to the Director of National Intelligence and the Secretary of Energy. A declassified and highly redacted copy of the DOE’s 2001 Classification Guide for Intelligence Information outlines the scope of the Office of Intelligence, specifically, within OICI. The document states that as a member of the Intelligence Community (IC), the DOE shall:

Participate with the Department of State in overtly collecting information with respect to foreign energy matters;

Produce and disseminate foreign intelligence necessary for the [Department of Energy] Secretary to fulfill his/her responsibilities;

Participate in formulating intelligence collection and analysis requirements where the special expert capability of the Department can contribute; and

Provide expert technical, analytical, and research capabilities to other agencies within the IC.

In 1999, Congress created another semi-autonomous DOE outfit known as the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) to oversee military applications of nuclear sciences. NNSA’s duties include maintaining and protecting the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile, attempting to counter nuclear proliferation, and responding to nuclear emergencies. NNSA is part of DOE, but operates with significant autonomy given its role and the sensitive nature of its work. There had even been an initial proposal to establish it as a completely independent entity. In yet another example of the many gray areas in terms of civilian vs. military control of the DOE, the first person to head up NNSA was John Alexander Gordon, a uniformed Air Force officer (who was also CIA Deputy Director at the time).

According to the FY 2021 Department of Energy budget request, NNSA requested over $26 billion in 2021 for defense activities, while $1 billion was requested for undisclosed “Other Defense Activities.” In 2017, the Congressional Research Service reported that roughly 3% of National Defense funding went to the Department of Energy and other federal agencies for “Atomic Energy Defense Activities,” which is one of NNSA’s primary tasks.

One of the other main objectives of NNSA is overseeing and operating some of the most secure facilities in the United States, including several national laboratories, the Nevada National Security Site, the Pantex Plant in Amarillo, Texas, which produces nuclear weapons, and the Y-12 National Security Complex near Oak Ridge, Tennessee, which produces all of the United States’ enriched uranium. Y-12 is also home to the production facility for the mysterious Fogbank, a material so sensitive to U.S. nuclear weapon technology that its manufacturing process, composition, use, and even the material itself remain classified. In fact, Fogbank is wrapped in so much secrecy that the DOE once “forgot” how to manufacture it due to a lack of actual records about how to make it and dwindling institutional knowledge as a result of read-in employees aging out of the workforce.

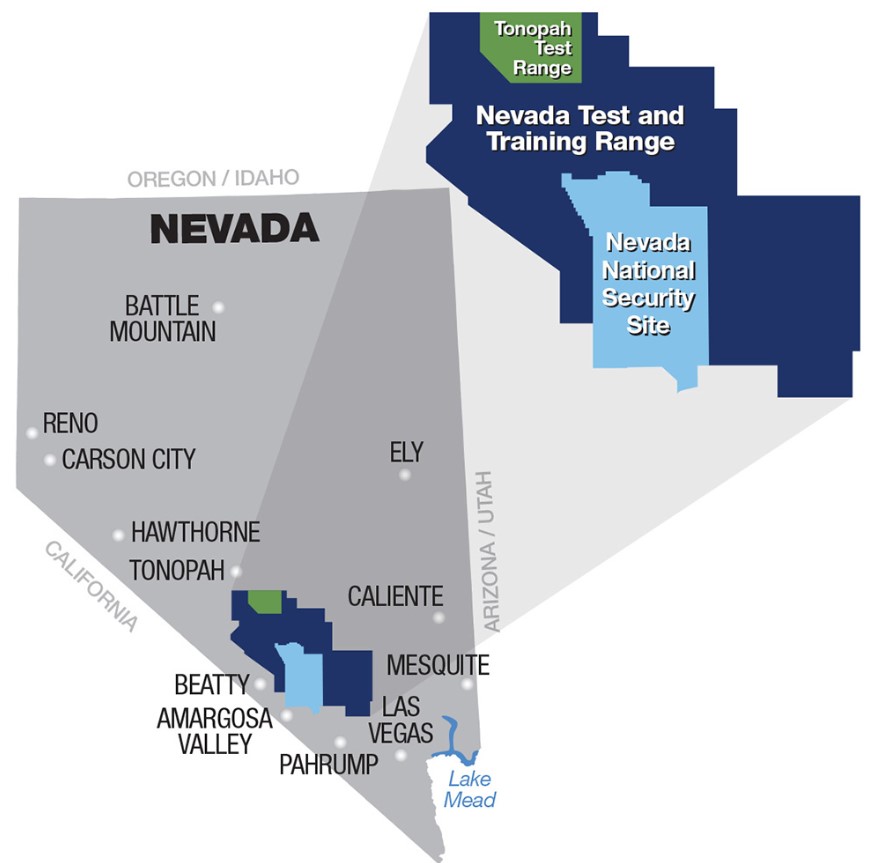

Among the other facilities the NNSA oversees is the Nevada National Security Site (NNSS), formerly known as the Nevada Test Site. The site, which boasts extreme security measures including its own security forces, stretches across some 1,400 square miles of desert and includes a nuclear weapons assembly plant, an experimental flight test facility, and explosive testing sites. The Air Force’s Nevada Test and Training Range (NTTR), which includes the notorious Area 51, surrounds the NNSS on three sides.

The Nevada National Security Site contains many DOE facilities for nuclear research including subcritical experiments and special nuclear material staging. The NNSS is also home to underground test facilities, and is among the United States’ most highly classified, restricted access areas. The NNSS offers limited tours, but these are conducted under the utmost security at pre-arranged times. During the Cold War, the Nevada Test Site, now NNSS, was home to hundreds of above-ground nuclear weapons tests which spread radioactive fallout across large swaths of the American West and Midwest. The DOE also maintains many “tombs” throughout the desert, where it stores the radioactive remains of nuclear experiments, spent nuclear fuel or enrichment products, and other remnants of America’s nuclear activities that are too dangerous to be disposed of anywhere else.

In another example of highly compartmentalized knowledge being lost due to workforce losses, a dismantling program had to be specially designed for the B53 nuclear bomb due to the fact that the scientists who knew its inner workings were either retired or dead. That program concluded in 2013 when the last one of these 10,000-pound bombs was successfully dismantled.

More recently, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) published the 2021 report “DOD and DOE Face Challenges Mitigating Risks to U.S. Deterrence Efforts” about the Nuclear Triad, which presently consists of Ohio class ballistic missile submarines, Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missiles, and B-2 and B-52 bomber aircraft. The GAO report found that DOE frequently “loses” valuable knowledge about its highly explosive weapon systems due to its knowledge base growing old:

As we reported in June 2019, there are about 100 different nuclear weapon components that contain explosive materials, some of which are highly specialized and limited in supply. For example, only a single container of one specialized material remains. DOE officials and contractor representatives said that the agency is working to replenish the supply of such materials, but the agency faces challenges because some specialized explosive materials were created decades ago, and the knowledge base to successfully produce them is now gone. Moreover, even if DOE can replicate the “lost recipes” for specialized explosive materials, it faces the challenge of finding suppliers willing and able to provide small quantities of specialized raw materials that meet the exacting standards required for use in nuclear weapons.

Clearly, the extent to which knowledge and operations within DOE are protected can make it difficult to understand or even be aware of the full scope of its activities. To help us contextualize the high levels of secrecy and classification at the Department of Energy, The War Zone spoke with nuclear historian Dr. Alex Wellerstein, Director of Science and Technology Studies at the Stevens Institute in New Jersey. Wellerstein’s latest book, Restricted Data: The History of Nuclear Secrecy in the United States, “traces the complex evolution of the US nuclear secrecy regime from the first whisper of the atomic bomb through the mounting tensions of the Cold War and into the early twenty-first century.”

Wellerstein told The War Zone that the levels of secrecy at the DOE are not common knowledge, saying:

I think most people are surprised to learn that there are basically two classification systems in the United States. There’s national defense information which is all the secrets and top secrets, everything to do with the military and the state department and all of that stuff, then there’s nuclear stuff. It has a different statutory basis, the Atomic Energy Act, it’s handled differently and conceived of differently by the Restricted Data clause, it has its own clearances, and is meant to be a parallel classification system. The fact that only nuclear weapons have this, that no other weapons technology has its own category – not even biological weapons or chemical weapons, they’re national defense information – is highly reflective of its origins in the Cold War.

When the first nuclear technologies were developed and the AEC was formed, the U.S. government saw a need for higher levels of secrecy in order to protect these terrifying new weapons. That’s not to say that those higher levels of secrecy were approved of by the entire government or even the AEC. “It’s been a point of contention since the very beginning whether this particular technology is so dangerous or so apt to carry secrets that it needs its own separate classification systems,” Wellerstein says. “The secrecy was created out of fear, out of a belief that nuclear technology could be easily communicated as information. Whether that’s true has been debated since the 1940s.”

Many experts have questioned whether these levels of extreme secrecy are beneficial or even needed. Many of the scientists working on the Manhattan Project or in science administration during World War II felt that secrecy would not be an effective way to control nuclear weapons, and that international agreements would ultimately be the only way. “Any competent nation with any sort of technical or industrial base would, if they devoted resources to it, would be able to reinvent them – even if the secrecy was total, which it wasn’t,” Wellerstein says. “I don’t think that secrecy is what keeps new nations from developing nuclear weapons and I don’t think it’s what’s keeping terrorists from getting nuclear weapons. I think its impact is not that large on preventing those kinds of things. Its impact on policy and public knowledge is very high by contrast.” Still, Wellerstein adds, “I’ve talked with government officials who emphasize that nuclear weapons are so disproportionately powerful that maybe it’s worth being disproportionately cautious about the unknown.”

Again, it’s natural that the DOE would not disclose specific parts of its most sensitive and dangerous weapons and associated technologies due to the ramifications of these potentially falling into the wrong hands. Still, by concealing many of its activities under the blanket of national security, NNSA and DOE leave plenty of room for activities or research programs that are never disclosed to the public.

The Question Of Oversight

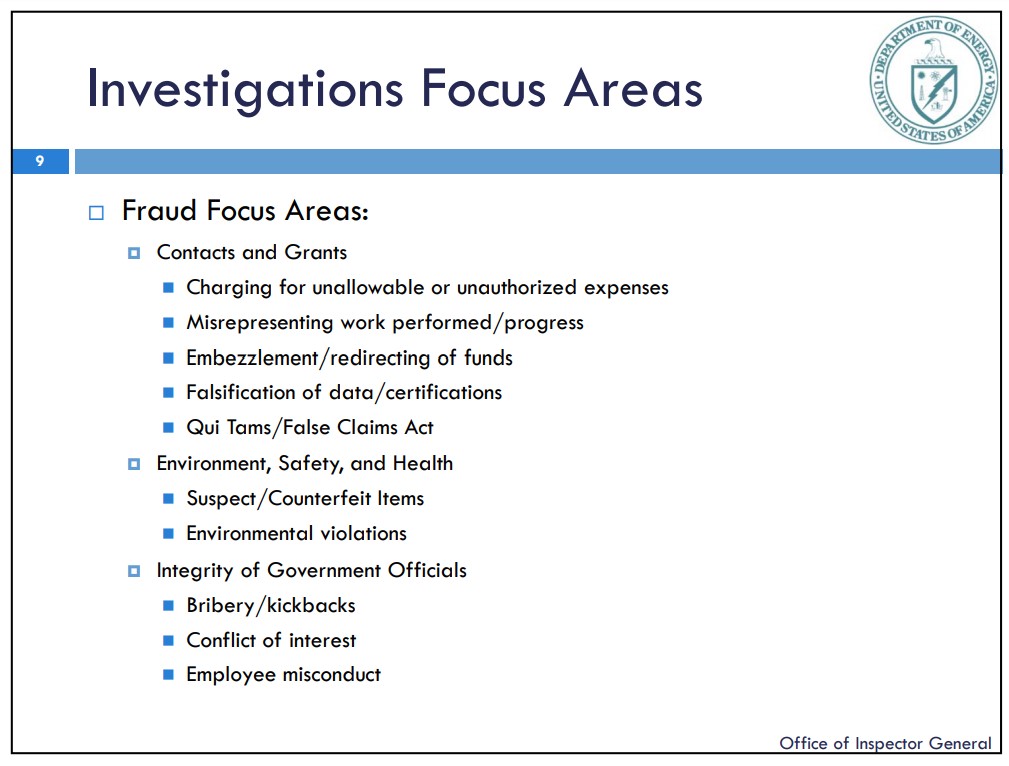

Even with the high level of compartmentalization and autonomy surrounding the DOE, as well as America’s nuclear weapons stockpile, the department has its own oversight bureaucracies, as well. After all, if you allow only the DOE to control and produce your nuclear weapons and related research, you also need your own separate oversight systems in place to watch over how that control and production is managed. To that end, the DOE has its own Office of Inspector General (DOE OIG), whose mission is to “help the Department and the American taxpayer” by identifying management shortfalls, assessing vulnerabilities, auditing the agency’s financial activities, and investigating crimes against the Department. The DOE OIG advises and makes key recommendations to the Secretary of Energy.

Aside from the OIG, the DOE is advised by the independent Federal Energy Regulation Commission, which oversees the transmission and sale of electricity and natural gas in interstate commerce, including oil pipelines. The DOE also has an Oversight Board, which monitors the environmental impacts of its operations specifically in New Mexico, including activities at Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), Sandia National Laboratories/New Mexico (SNL/NM), and the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP).

There are a variety of mechanisms through which the U.S. government exercises oversight of the DOE and NNSA. The U.S. Congress, for one, has two subcommittees devoted to energy-related issues including nuclear weapons and facilities. The Energy Subcommittee of the House Energy and Commerce Committee and the Subcommittee on Energy of the Senate Committee on Energy and National Resources oversee the creation of legislation regarding a wide range of energy issues beyond nuclear matters alone. The House’s Energy Subcommittee oversees nuclear energy, nuclear facilities, the Department of Energy, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, while also legislating on national energy policy, fossil fuels, and other government activities affecting energy matters. While the Senate’s Subcommittee on Energy has oversight jurisdiction over nuclear fuels research and development, nuclear commercialization projects, nuclear fuel cycle policy, and the DOE National Laboratories, it also oversees energy-related issues such as fossil fuel management, pipeline development, strategic fuel reserves, and sustainable energy research.

Steven Aftergood told The War Zone that, while there are Congressional structures in place to provide oversight of the DOE, “the quality of oversight depends on many factors, including Members’ level of interest, the expertise of committee staff, the cooperation of the agency, and the attention of the press and public interest organizations… With respect to secrecy and classification at DOE, my impression is that congressional oversight is nearly non-existent. But that is true regarding classification policy across the board.”

It is certainly true that these committees have a huge portfolio and it isn’t clear how they would effectively oversee a huge swathe of deeply classified programs the DOE is executing at any given time, some of which have many sub-programs and unique facets beyond their topline justification.

To bolster DOE oversight, Congress established the Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board (DNFSB) in 1988 as an independent organization that would provide oversight of the DOE’s nuclear production and testing facilities. Through this board, Congress is theoretically granted oversight of the DOE’s and NNSA’s operations and management, and Congress is responsible for the authorization and appropriation of funds for America’s Nuclear Security Enterprise. The DNFSB was set up as an independent oversight organization, which would offer recommendations to the Secretary of Energy that concerned public health and safety at the DOE’s nuclear weapons complex. Members of the board are appointed by the U.S. Senate. A full record of correspondence between the DOE and the DNFSB can be found on the DOE’s website, including all recommendations the board made between 2012 and today.

That doesn’t mean the DNFSB has always had full cooperation from the DOE. As recently as 2018, there were complaints that the DOE was stonewalling the DNFSB and preventing it from carrying out its oversight duties. According to one Senate staffer who helped draft the original DNFSB legislation, the DOE was trying to “isolate and fence off” the board, as part of a “constant effort to chip away at the ability of the board to do oversight.” There have even been calls from within the board to abolish itself entirely, and the NNSA has frequently tried to limit the board’s access to information.

A DOE special investigative panel concluded in 1999 that the department is “a dysfunctional bureaucracy that has proven it is incapable of reforming itself” and that “accountability at DOE has been spread so thinly and erratically that it is now almost impossible to find.” The panel added that, “Never before has the panel found an agency with the bureaucratic insolence to dispute, delay, and resist implementation of a Presidential directive on security,” and that “Never have the members of the Special Investigative Panel witnessed a bureaucratic culture so thoroughly saturated with cynicism and disregard for authority.”

One reason for this dysfunction could be that on the legislative side, the DOE does not get the public or official scrutiny the DOD or the IC gets. “What’s interesting to me about the AEC and the DOE is that unlike a lot of federal agencies, they don’t have natural allies in the political ecosystem,” Dr. Alex Wellerstein told The War Zone. “They don’t have a constituency in the same way that, say, the Dept. of Agriculture does, or how the DOD has the military, for example.”

Bruce Hamilton, who at the time was chair of the Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board, said DOE officials routinely flout new regulations which were to limit the amount of information that the DNFSB could obtain directly from nuclear facilities and instead restrict the board from obtaining the same information directly from DOE administration. “We have repeatedly heard from DOE representatives that they really don’t mean what they wrote (in the rule) or at least that they really don’t intend to follow what they wrote,” said Hamilton, adding that this is a “particularly bizarre argument coming out of the nuclear culture that has set the standard for following the written rules to the letter.” Those new measures, outlined in DOE Order 140.1 A, also excluded many of the DOE’s weapons complex facilities from DNFSB’s formal safety recommendations, and changed the definition of “public health and safety” under DNFSB oversight to exclude the safety of workers at nuclear facilities

In 2020, the ranking member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, Jim Inhofe, an Oklahoma Republican, even went so far as to accuse DOE officials of being “rogue actors” who to “undermine” the security of America’s nuclear activities. The Department of Energy Organization and Management Improvement Act, introduced in the House in September 2020 by then-Representative Greg Walden, an Oregon Republican, would, if made law, give the DOE even more control over the NNSA. This means it could operate with even less government oversight than it already has now.

Holding The Keys To America’s Most Sensitive Research

Aside from developing and maintaining the United States nuclear weapons stockpile, there is a great deal of advanced research being performed at Department of Energy laboratories, including pioneering work on some of the most cutting-edge topics science has to offer. Nearly $5.9 billion was allocated to the DOE’s Office of Science (SC) in 2021 to “deliver scientific discoveries and major scientific tools to transform our understanding of nature and advance the energy, economic and national security of the United States.”

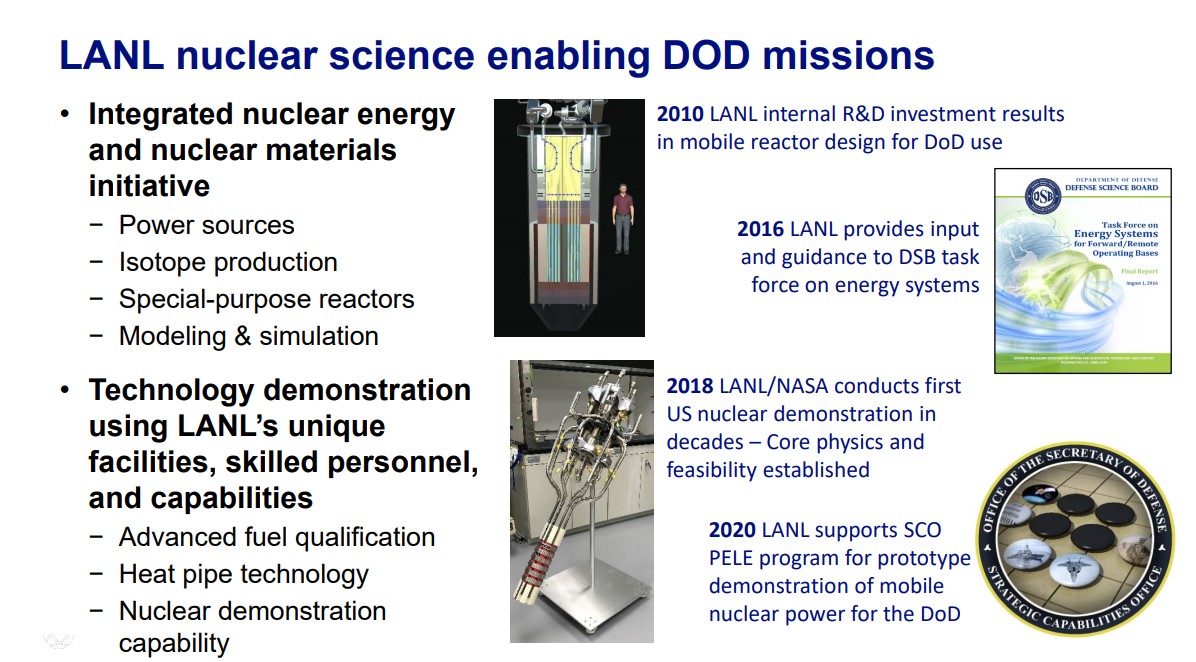

A large part of this research is conducted at the 17 United States Department of Energy National Laboratories and Technology Centers, which are spread across the country. Much of the research and technology development conducted at these labs goes straight to the DOD: LANL has conducted space-based directed energy weapon experiments for the Missile Defense Agency (MDA); the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) has developed advanced munitions for the Air Force; Sandia has had a hand in producing some of America’s first hypersonic weapon prototypes.

One of the reasons why the DOE-controlled laboratories develop advanced weapons technologies designed for transfer to the DOD is that they, as well as various other facilities today under NNSA, have the capacity for specialized research and development and unique manufacturing work that just cannot be done in many places. If you need to do novel manufacturing on a large scale, and are looking to do so within a system that already has significant security measures in place, the DOE laboratories are the place to go, and it’s been that way for decades.

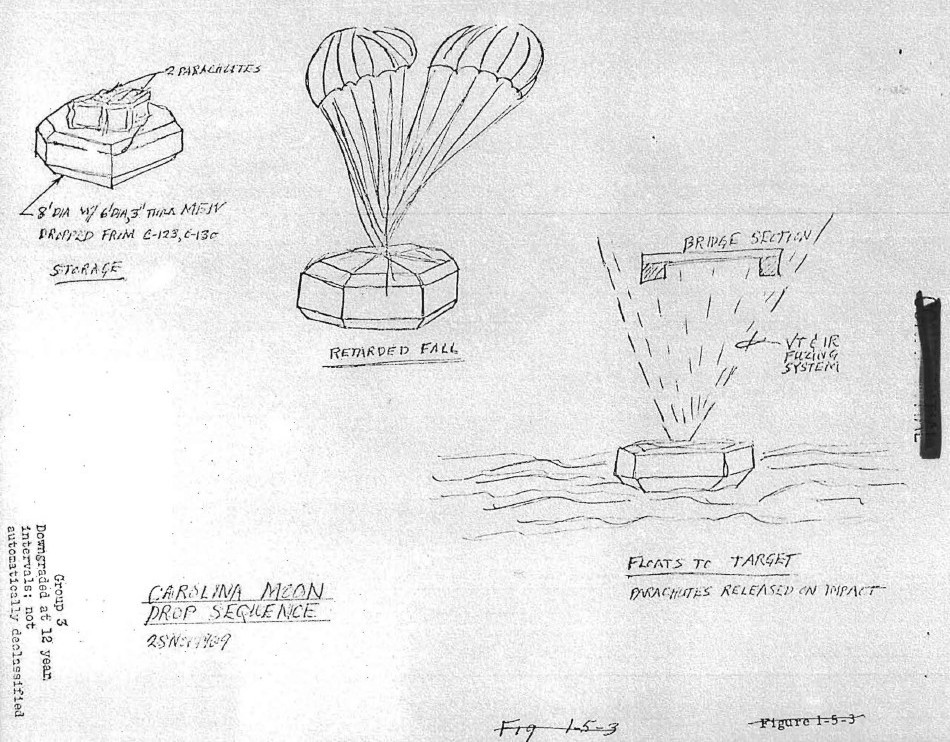

For instance, when the Air Force decided to try using massive floating bombs during the Vietnam War to blow up the Thanh Hoa bridge, there was simply no one else within the national security apparatus besides Y-12 at Oak Ridge that could build large metal structures to the kind of exacting specifications the service needed. Some details of that top-secret mission, known as Operation Carolina Moon, are still classified.

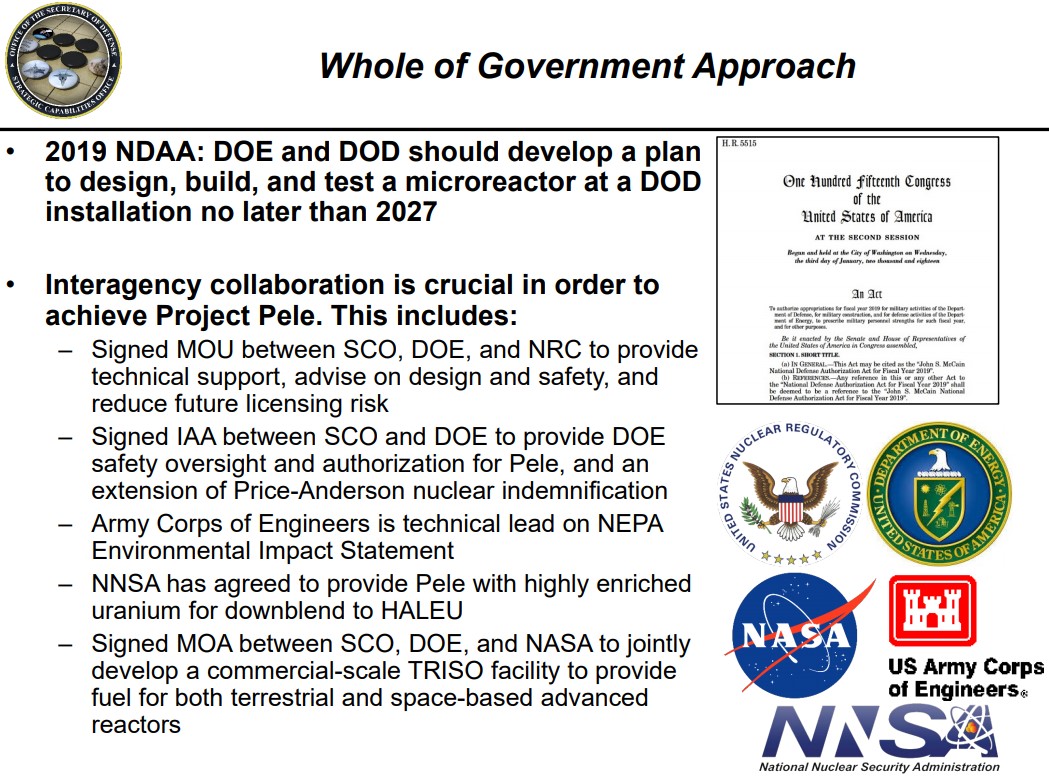

More recently, the DOE signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Department of Defense to confirm and enhance the “the longstanding partnership between DOE and DOD on space-related research and technology development in support of U.S. national space policy goals.” In a press release that accompanied the MOU, then-Deputy Secretary of Energy Mark Menezes called the agreement “historic,” and claimed it “lays out the framework for DOE to harness the world’s greatest science and technology researchers at DOE’s National Labs, and program offices, to augment DOD’s critical national security space mission and will play a crucial role for future space developments across the two departments.”

More specifically, the MOU establishes joint working groups and promotes scientific exchange between the two departments in emerging and disruptive research fields such as advanced power and propulsion, artificial intelligence, quantum computing, next-generation communications, and autonomous or remotely piloted vehicles. That MOU came on the heels of one of President Donald Trump’s final Executive Orders that called for the DOE to work together with NASA and the Department of Defense to research and develop miniaturized nuclear reactor technologies for space exploration and powering military bases.

The DOE also currently operates a Fusion Energy Sciences (FES) program, an Advanced Scientific Computing Research (ASCR) program, and a Nuclear Sciences program, the latter of which seeks to put together “a roadmap of matter that will help unlock the secrets of how the universe is put together.” To that end, in April 2020, the DOE put together a 10-year plan to invest in plasma physics research encompassing both “discovery” plasma sciences, which involves understanding the properties of plasma and non-energy applications of plasmas; and fusion science and technology, which is related to fusion energy generation. “Research in high energy physics not only advances our understanding of the universe, but is also critical to maintaining American leadership in science,” former Under Secretary of Energy for Science Paul Dabbar said in a 2019 DOE press release. “These research efforts, at dozens of universities across the nation, will not only yield fresh insights into such problems as dark matter and dark energy, but also help build and sustain the nation’s science and technology workforce.”

DOE also funds research initiatives in sustainable and alternative energies, AI and machine learning, quantum computing, and even genomics, one of the more controversial areas of its scientific endeavors. According to the “Genomics” section on Energy.gov, the Human Genome Project was initially launched by DOE to better understand the genetic effects of radiation exposure, “but there was clear awareness that success in the project would have much broader consequences for both science and society.”

DOE has quite a checkered past when it comes to its biological experimentation. In 1994, then-President Bill Clinton formed an advisory committee to look into DOE’s human radiation experiments, releasing nearly two million pages of formerly classified documents that detailed unwitting human test subjects such as orphans, hospital patients, or mentally disabled children being fed or injected radioactive materials.

In the Executive Summary released by the Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments, it was reported that close to 4,000 human radiation experiments were carried out by the U.S. government between 1944 and 1974. The Committee’s report was conveniently, or coincidentally, released by the White House on Tuesday, October 3, 1995, the same day that the O.J. Simpson murder trial verdict was announced.

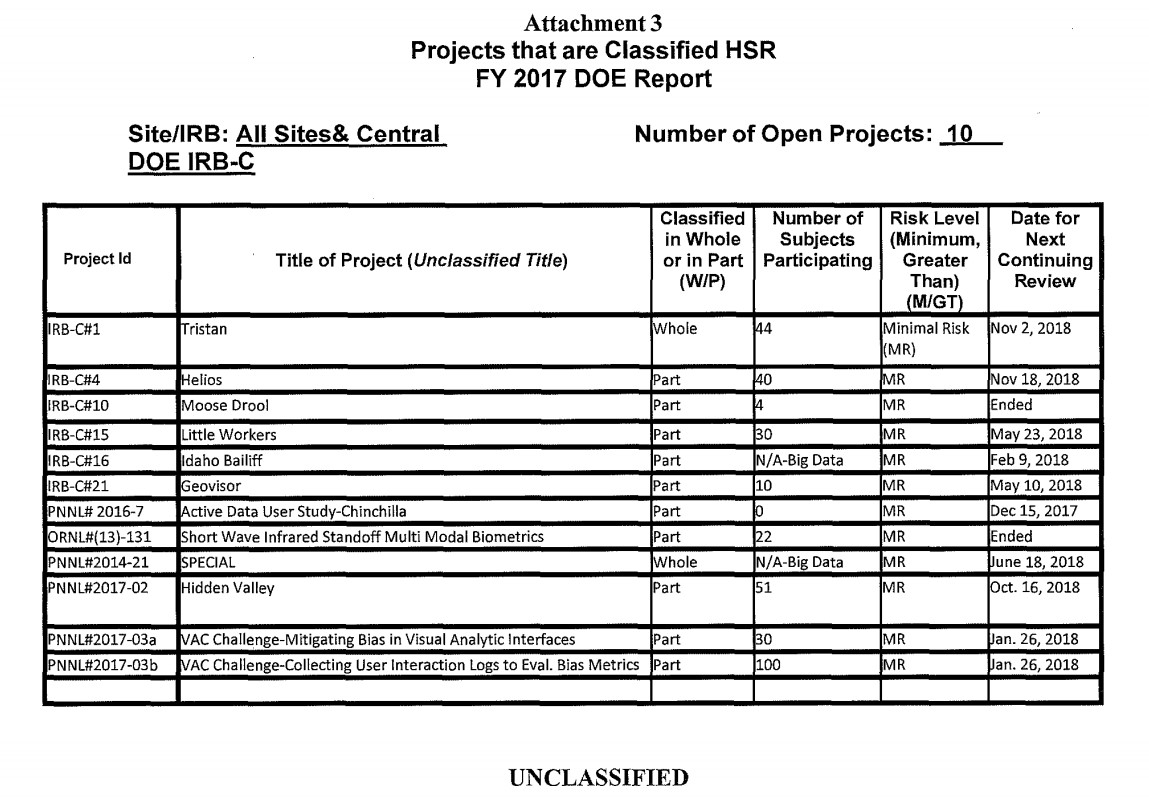

That report did not stop DOE’s interest in human subject research (HSR). As recently as 2018, it was still actively conducting classified research on human subjects, arguing that “research using human subjects provides important medical and scientific benefits to individuals and to society.” Because many of these projects use code names such as “Moose Drool” and “Little Workers,” it’s unknown what exactly they are studying with these human subjects.

When it comes to whether there is a chance that advanced energy research or other groundbreaking scientific breakthroughs could possibly be locked away deep behind DOE secrecy, Wellerstein told The War Zone it’s certainly possible, although it’s more likely funding, rather than secrecy, is what keeps these programs in the dark. “It’s possible, although a lot of the peaceful aspects have been declassified over the years starting in the 1950s. Whether that’s all been beneficial or not is a topic for debate since a lot of those things are dual-use, like reactors. But it’s always possible. The most important thing for the development of reactor technology or say, nuclear fusion, is less the classification, but funding.”

Wellerstein told The War Zone that there are plenty of avenues by which the DOE might use its budget for classified or non-disclosed activities. According to the FY 2021 DOE budget request, for example, the NNSA was allocated $15.6 billion for “Weapons Activities to maintain the safety, security, and effectiveness of the nuclear stockpile, continue the nuclear modernization program, and modernize and recapitalize NNSA’s nuclear security infrastructure portfolio.” In the volume of the budget request dedicated to descriptions of the NNSA’s spending, there is little clarification as to the specific technologies and capabilities the NNSA is developing:

The Weapon Technology and Manufacturing Maturation program is responsible for developing agile, affordable, assured, and responsive technologies and capabilities for nuclear stockpile sustainment and modernization to enable Defense Programs’ mission success and the future success of the NSE [Nuclear Security Enterprise] and will continue these activities in FY 2021. The core areas of work include agile, assured, and affordable technologies; partnership with stakeholders to meet stockpile and customer requirements; qualification and certification; and skilled technical workforce and enhanced capabilities.

Keepers of America’s Secrets

With both the extreme levels of secrecy surrounding much of the Department of Energy’s research and even the scope of DOE’s research, it’s possible, if not probable, that there are more radical and more exotic developments than these hidden behind the doors of DOE laboratories. It would be hard to argue that breakthroughs in advanced physics, nuclear aerospace propulsion, or energy production would live somewhere other than the Department of Energy. While that much may ultimately be impossible to verify, it certainly seems possible that the DOE could conceal such a breakthrough given how compartmentalized and classified much of its work remains and how specialized and advanced its facilities are. And once again, while maintaining a very close relationship with the U.S. military, as the two institutions are tied together strategically very tightly, the DOE really doesn’t get the attention the DOD does and that may be true in terms of oversight, as well.

Still, it makes complete sense that DOE would be one of the most secretive departments of the United States government. Nuclear technologies are among the most dangerous and sensitive in the world, and the risk of nuclear weaponry falling into the wrong hands remains near the top of the most pressing threats faced by the modern world. But more so, the nuclear secrets that underpin America’s nuclear deterrent, as well as those that could define it in the future, would be considered among the country’s ‘crown jewels’ when it comes to sensitive technologies.

All this seems to provide a uniquely fertile and undisturbed environment in which bringing new, highly powerful, and potentially very destructive technologies from concept to reality could flourish. In fact, one could argue that is historically bred right into the DNA of the agency. Unfortunately, all this is hard to quantify, but then again, that seems to be the point.