POST & COURIER SPECIAL REPORT: LETHAL LEGACY

BY THAD MOORE & COLIN DEMAREST | postandcourier.com

South Carolina could be stuck with a massive stockpile of the nation’s most dangerous nuclear material for decades, despite a federal mandate and years of promises that the state wouldn’t become America’s plutonium dumping ground.

A restricted internal report obtained by the Aiken Standard and The Post and Courier suggests that the state is likely to become a long-term repository for enough plutonium to build the bomb dropped on Nagasaki nearly 2,000 times over.

A restricted internal report obtained by the Aiken Standard and The Post and Courier suggests that the state is likely to become a long-term repository for enough plutonium to build the bomb dropped on Nagasaki nearly 2,000 times over.

South Carolina faces this prospect despite a federal law that gives the U.S. Department of Energy just 2½ more years to remove its plutonium from the Savannah River Site, a huge swath of federal land along the Georgia border.

The report, written last November by the Energy Department and a project-management contractor, reveals that the government privately expects South Carolina to safeguard the legacy of America’s nuclear brinksmanship for two more decades, if not longer.

That plutonium is stored in a 65-year-old, Cold War-era building just 25 miles from Aiken and downtown Augusta, which anchor a region of more than 600,000 people. The Energy Department once told South Carolina’s governor it wasn’t intended for long-term plutonium storage. The last time the government assessed it, it was in “poor” condition.

It would take a decade just for workers to pack up the plutonium and send it away on dozens of truck convoys, the report says. And the government wouldn’t be able to start that work until it had prepared another facility to store the material, adding years to its stay in South Carolina.

The report suggests for the first time that the nation’s excess plutonium could be eventually consolidated in one place: the Pantex Plant in the Texas panhandle, one of the only places in the U.S. with a bigger stockpile than South Carolina. Other states are wary of inheriting South Carolina’s role decades from now; Nevada has already mounted a legal fight to avoid it.

Wherever it goes, the report shows that the last of the plutonium is unlikely to leave South Carolina until at least 2037 — almost 40 years after federal officials promised it wouldn’t be here long. It will stay into the 2040s if the government follows through with plans to process the stockpile and render it less dangerous, work that won’t begin in earnest for another nine years.

The issue is coming to a head now because the federal government last year abandoned a plan to make fuel for power plants out of plutonium, a substance otherwise used to trigger nuclear explosions. Nearly $8 billion and 11 years into that project, officials decided that a new processing plant would be too expensive to finish because of spiraling costs and mounting delays. More than 1,000 workers lost their jobs.

Their decision fulfilled a prediction made by former Gov. Jim Hodges years earlier in 2002, before the Department of Energy had its weapons plants and laboratories send their unneeded plutonium to the Savannah River Site.

“Once plutonium arrives, it will never leave,” he said at a press conference shortly before the first trucks rolled in. “They want South Carolina to quietly become the nation’s plutonium dumping ground. This plutonium will be stored indefinitely in buildings not intended for storage, and processed in a facility that will likely never be built.”

Hodges was deep into a fight to keep plutonium from coming across the state line until there was a backup plan to get it out. He was announcing a last-ditch effort to hold up shipments: an executive order that banned plutonium on South Carolina’s roads and dispatched troopers to look for it.

It didn’t work. Just days after Hodges made his prediction, a federal judge struck the order down. Judge Cameron Currie told the governor not to get in the way of a plutonium shipment again, and she scolded him in open court for not respecting the U.S. Constitution.

Federal law supersedes the state’s wishes, she said, and the law gives the Energy Department wide latitude.

Which is to say, South Carolina might not want the nation’s plutonium, but it could be stuck with it.

The forever problem

German blitzkrieg had ripped through Western Europe, bombs had been falling on London for months, but World War II had not reached America by the end of 1940.

Christmas wasn’t two weeks away, and in the face of escalating combat, a group of scientists gathered in a California lab to create the first fleck of America’s eternal mess.

The scientists blasted a piece of uranium with a special kind of hydrogen until neutrons pierced its atoms and began transforming it into a new element: plutonium.

They didn’t know it then, but the microscopic speck of metal they created would transform the American race to build a nuclear bomb. It held immense power — the power to destroy cities in an instant. In the fervor of wartime and the Red Scare, the U.S. would make more than 100 metric tons of it, first as war racked the world, then in a nuclear standoff with the Soviets.

Each new ton compounded a profound dilemma that the U.S. has failed to resolve since the end of the Cold War: Plutonium won’t go away on its own. The nation has had plutonium for less than 80 years, hardly a blink in the life of an element that will survive for millennia.

It will take 24,000 years for the plutonium in South Carolina to lose half its potency, which is twice as long as humans have been farming. And it will take 10 cycles of decay, or 240,000 years, for it go away entirely. Homo sapiens emerged as a species about 300,000 years ago. Even then, it will transform into a kind of uranium used in nuclear weapons.

It’s an eternity of power that derives from plutonium’s instability.

When enough of it is put together, it only takes one atom to cause a violent chain reaction. A splitting atom shoots out neutrons, hitting the atoms around it and causing them to burst, hitting more atoms still. Each rupturing atom unleashes the energy that held it together.

The U.S. has only used a plutonium bomb once — the “Fat Man,” over Nagasaki, Japan. Its plutonium core was no bigger than a softball, according to the Atomic Heritage Foundation. Of the roughly 6 kilograms inside, only one reacted. The U.S. government would later estimate that at least 39,000 people died as their city crumbled.

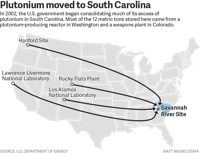

In South Carolina, the government keeps some 12,000 kilograms of its excess plutonium at the Savannah River Site, much of it made here during the Cold War. The rest is a mix of powder and metal chunks that came from weapons plants and laboratories in Washington and Colorado, California and New Mexico.

It came here to be repurposed. Before South Carolina became one of America’s biggest plutonium warehouses, it had hoped to be its recycling plant. It signed up to turn weapons-grade metal into fuel for nuclear power plants by mixing it with uranium and pressing it into pellets. It’s a complicated process called mixed oxide fuel fabrication, or MOX for short.

South Carolina’s leaders in the late 1990s wanted to guarantee a future for one of the state’s largest employers, the Savannah River Site, as the country shifted away from building new weapons. The Department of Energy insisted that plutonium storage had to be part of the deal. It was eager to consolidate its stockpile because it would be cheaper and safer to protect one site instead of many.

The bargain fell apart last year when the government decided that MOX was too expensive. American taxpayers had already spent nearly $8 billion on the project, and the Energy Department expected to spend tens of billions more before the plutonium was all gone.

“We took a national problem, which was the safe disposition of plutonium, and we made it a South Carolina problem,” Hodges said in an interview last month. “We’re left holding the bag for a significant national issue.”

A concrete tomb

The stockpile now sits on the southern half of the Savannah River Site, a federal installation ringed by pine trees and a twisting river, beside a curl of small towns like Allendale and Barnwell and the horse country around Aiken.

It’s stored about 5 miles from the Savannah River itself in what the government calls the K Area but officials sometimes call the “Fort Knox of plutonium.” It’s a reactor building that produced bomb-making material during the Cold War and now stores it in thousands of steel drums, stacked three high.

The reactor opened in 1954, just a few years after the government created the site by seizing a swath of land more than three times the size of Lake Moultrie. If the building were a person, it would receive its first Social Security check next year.

It has shown its age for close to two decades — even before plutonium came to South Carolina. A government contractor wrote in 2000 that concrete was flaking off and falling, according to a report uncovered in the state’s archives. It said it was “virtually impossible” to know how long a concrete nuclear facility would last.

But the contractor gave the Energy Department the go-ahead to use the building. The cracks in the walls and ceilings weren’t growing, it reasoned, and the worst issues weren’t in the plutonium vault.

With the plutonium inside, the reactor became cloaked in intense security and secrecy. The government doesn’t even allow visitors to photograph the exterior. The public gets few glimpses of what’s happening inside.

Most come from an obscure government agency that keeps an eye on the government’s nuclear infrastructure. The Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board is small but independent, a panel of nuclear experts appointed by the president to weigh in on the Energy Department’s work.

The agency keeps a pair of inspectors at the Savannah River Site, who occasionally write terse public updates about the K Area and the ways it has aged.

They wrote about how the roof could collapse if a forklift crashed into the wrong column, and how a 60-year-old transformer failed in 2011, cutting power for hours and leaving workers without working radios or phones.

They wrote about how workers found a broken metal rod sticking out of a wall in 2014, apparently part of the building’s fortification against earthquakes, and how the engineers were studying if more might fail.

They wrote that six concrete panels had collapsed in 2016 because they weren’t rated for heavy wind, leaving “a large hole in the wall near the roof” in a room slated to store processed plutonium.

Their thoughts sometimes turned to the worst-case scenarios, like the prospect of a fire, and the ways the building would be vulnerable. Nuclear watchdogs worry that if a fire got big enough and the storage containers failed, flecks of plutonium could become airborne and South Carolina would face an environmental disaster, at best.

“It doesn’t take a lot of plutonium to create a big environmental crisis,” said Edwin Lyman, acting director of the Union of Concerned Scientists’ nuclear safety project. “If it’s not a major health threat to the public, it would at least cause a huge cleanup crisis at the site.”

The safety board found that the government wasn’t rigorous enough in maintaining the K Area’s water supply for fighting fires and addressing its “numerous deficiencies,” it said in 2012. The facility had sediment building up in its only source of water and pumps that were deteriorating and moving less of it. The department says it cleaned out the tank and replaced the pumps.

The board wrote in 2010 that the building’s water mains were laid out in straight lines, not loops, meaning parts of the system would be vulnerable if a pipe broke. The Energy Department doesn’t have sprinklers throughout the building, and it decided it didn’t need them outside of the areas where workers handle plutonium. In 2007, the safety board settled for a fire detection system instead.

If a fire broke out, the emergency plan would rely on the site’s fire department to douse the flames. But recently, the Energy Department has acknowledged that firefighters could face “significant obstacles” inside the storage building, according to a 2017 report by a department oversight group. They’d have to pull hoses hundreds of feet “through multiple corridors, stairwells, doors and processing areas by hand,” moving through contaminated air.

The department says its specialized steel drums would protect the plutonium for at least an hour and a half if there was a fire, and it thinks it’s exceedingly unlikely that any would be released. Its analysis found that it would take a worse-than-expected earthquake and a fire to trigger a radioactive release.

The department also says it has taken steps to fix the building’s most pressing problems, like replacing the fallen concrete panels, repairing the earthquake defenses and putting up barriers around support columns. And it says two of its national laboratories are monitoring conditions.

But even the department has indicated that the building isn’t in great shape, according to a 2015 report on the Savannah River Site’s facilities. It described the state of every building in a word.

It said the old reactor’s condition was “poor.”

A short-term fix

The government has admitted that the reactor building wasn’t meant to be more than a stopgap measure.

Former Energy Secretary Spencer Abraham said as much before his department shipped plutonium here, saying in a 2002 letter to Hodges that it was “not intended for use as a long-term storage facility.” Even today, the department says the building is only meant to hold plutonium that’s “awaiting processing.”

But a more permanent solution is distant.

The government appears to be zeroing in on a plan to build a new underground bunker in the Texas plains with room to take weapons, spare parts and South Carolina’s plutonium, according to the report obtained by the Aiken Standard and The Post and Courier. It wouldn’t be able to take the entire plutonium stockpile for another 20 years.

The department’s nuclear-weapons agency says it’s in the “early planning stages” of such a project, but it says it’s too soon to say if South Carolina’s plutonium stockpile will go to Texas.

If those plans come to pass, the government would give nuclear watchdogs something they’ve long wanted: a plutonium storage building that was actually designed to store plutonium.

It has considered building one before. The Energy Department designed a building that could stabilize plutonium metal to make it less volatile, then store it while MOX was being built. It had even started to excavate the site.

Then it changed its mind. It decided to depend on MOX to process the plutonium rather than build an extra facility to store it. If its plans to recycle plutonium worked, a brand-new storage building would be unnecessary. Doing without one would save hundreds of millions of dollars.

“DOE cut corners everywhere it could,” said Tom Clements, a longtime nuclear watchdog who runs the public-interest group SRS Watch. He said killing the storage building was one of the biggest ones. It left the plutonium in “a jury-rigged facility of convenience,” Lyman said.

The Energy Department’s rationale drew objection after objection from the government’s nuclear safety board in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The board’s chairman wrote that the government’s choice “disrupted well-founded plans” for storing plutonium.

The board warned that using old facilities for the job would be impractical, that the K Area buildings weren’t intended for anything more than temporary storage. It said the Energy Department shouldn’t bank on risky processing plans like MOX to succeed and fix its nuclear storage problems. And it said it shouldn’t walk away from long-term solutions because of short-term budget considerations.

The safety board wrote annual reports about the reactor building at the request of Congress, which asked it to list its concerns and follow up until they were resolved. The board wanted the Energy Department to consider a dedicated storage building, but it dropped the issue in 2006.

A new building would be needless, it finally agreed, “if current plans for storage and potential disposition are met.” Those plans weren’t met, but the board hasn’t addressed the issue publicly since the MOX project was called off. The board’s three sitting members declined to be interviewed for this article.

‘Potentially at risk’

The government now has little choice but to keep the K Area functional.

The Energy Department has said in planning documents that failure is not an option because there is no real backup plan if the storage facility has to close. All it can do is maintain the building well enough to “reduce the probability” of a major problem.

That will be an expensive task. The government’s most recent estimates show that it would cost nearly $61 million just to catch up on the maintenance work that had been put off in the K Area’s mission-critical buildings. A contractor identified dozens of needed projects in 2015. Many of them addressed the facility’s most basic functions, like replacing “degraded” roofs and providing “reliable power.”

The department says it has finished some of those projects, like fixing the electrical system, and it’s working on several more, like replacing some roofs. When the building is reassessed this year, it says it should get an “excellent” rating. That’s partly because the grade is based on what it would cost to replace the building outright and its estimates have changed.

The K Area is one of the many challenges bearing down on America’s nuclear weapons complex.

The infrastructure of nuclear bombs is much the same as it was during the escalation of the Cold War. Some of it dates to World War II. It relies on the same once-secret towns and government installations and many of the same buildings.

Those buildings are getting old.

The Energy Department said last year that 40 percent of its plutonium-handling facilities are considered inadequate. It gave similar marks to the buildings where it works on nonproliferation, uranium, and protecting nuclear materials.

The low marks mean that each of those programs — among its most sensitive — are considered “potentially at risk” by the department’s own definition.

It says so in annual reports about its facilities, in which it repeats the same refrain each year: that it has “a systemic challenge of degrading infrastructure” and growing maintenance needs.

“The country is going to hit a wall in the not too distant future with respect to large portions of our national security infrastructure,” said John MacWilliams, who was the department’s first-ever chief risk officer in the Obama administration. “These bills are coming due and we need to find more creative ways to finance infrastructure.”

Overdue maintenance in the nation’s nuclear program alone totals $2.5 billion, inching up last year despite efforts to rein it in. The mass of needed work is hardly an anomaly across the Energy Department, where only about half of all buildings are rated adequate.

Even so, the nuclear weapons program has projected only modest increases to its maintenance spending over the next several years, in spite of what its annual budget request calls a “long-standing deficiency” in its building upkeep. The department says it needs time to staff up so it can make use of more funding.

“This is not something we can do overnight. It will take decades to modernize our infrastructure, but it is critical that we do so now,” Lisa Gordon-Hagerty, the head of the nation’s nuclear security program, said last year. She was asking Congress for a “sustained” flow of money for infrastructure projects. “We are at a point where we have no more margin for error or for doing nothing.”

The nuclear complex’s observers say the Energy Department’s pinched budget has consequences beyond its buildings. Congress funds its work and its projects year to year, which narrows its outlook and often leaves it to work with what it already has.

It’s dealing with substances that could last longer than humanity. But as it navigates the whims of each new Congress and president, it’s only positioned to make decisions for the short term.

“Long-term planning has never been DOE’s strong suit,” said Lyman of the Union of Concerned Scientists. “They’re responding to near-term crises.”

The question is, how much of a problem will keeping plutonium in South Carolina be?

The fight

When plutonium shipments first arrived in South Carolina in 2002, its leaders mounted an all-out effort to make keeping the material here a problem for Washington.

Gov. Hodges spent months trying to drum up public attention as he negotiated the terms of the plutonium’s stay here. He ran TV ads, ordered state police to practice a plutonium blockade and vowed to lie down on the highway to block the nuclear convoys.

The Energy Department finally offered concessions that would have had the stockpile out by now, but its proposal didn’t have the full force of law.

Abraham, the energy secretary at the time, told the governor that what the deal lacked in legal safeguards, it came with political protection. It was “the kind of commitment that an Administration walks away from unilaterally only at considerable political peril,” he wrote in a letter to Hodges.

He played hardball and told Hodges to take the offer or get the plutonium anyway. Either way, he was going to clear shipments to South Carolina.

Hodges resisted. A decision politically perilous to one administration might not be to the next, and plutonium would outlast any president.

“Memories fade and people change,” Hodges said in June. “It was a take it or leave it ultimatum, and our view was leave it.”

The showdown culminated in Hodges’ lawsuit against the Energy Department. A group of businessmen and civic leaders from the site’s rural fringe tried to join his effort, fearing they might bear the risks of storing America’s nuclear excess without being compensated for it.

Danny Black was one of them. He still worries about the effect the plutonium stockpile is having on Barnwell County, where he runs an economic-development group.

He hears about it when industry considers opening a factory there, how they wonder if it’s safe to operate nearby. Companies like food processors have been especially wary. He says he wishes the government would put the material in a permanent facility if it’s going to stay.

“You’ve got all this plutonium down the street, and people think about that,” said Black, the CEO of the SouthernCarolina Alliance. “It’s sitting here, and there’s nowhere for it to go.”

The local leaders argued that South Carolinians should be paid for the economic risks, but their fight didn’t last long. Judge Currie decided within days that the group didn’t meet the legal standards for joining the case.

And by then, the state’s showdown was already racing to its end. Two weeks later, the governor’s plutonium blockade was struck down.

A broken trust

Later that year, Congress stepped in. South Carolina’s delegation, led by Sen. Strom Thurmond, had protections for the state enshrined in federal law.

Congress set deadlines for the plutonium to be removed — it’s supposed to be out by January 2022 — and established $100 million-a-year fines for the Energy Department if MOX didn’t start up on time.

The state has used that law extensively: It has sued the federal government five times, trying first to keep the government from cancelling the MOX project, then to have plutonium removed, then to claim $200 million in unpaid penalties.

The state hasn’t been paid any fines, and has managed so far to win a court order to have 1 metric ton of plutonium removed. The courts haven’t addressed the rest of the plutonium.

It has threatened to sue again, according to a letter obtained under an open-records request. South Carolina’s attorney general, Alan Wilson, wrote U.S. Attorney General Bill Barr in March to say he “anticipates engaging in additional litigation” to have more plutonium removed unless they reach a settlement.

The state’s threat came only a few months after an October meeting between President Donald Trump, South Carolina’s leaders and top Energy Department officials. They met for a half-hour in the Roosevelt Room of the West Wing to talk about the MOX project and the future of the plutonium stockpile. Trump asked whether it would stay in South Carolina.

Department officials assured the president that plutonium was on its way out of the state, Gov. Henry McMaster recalled in an interview in June. They were apparently referring to the metric ton a federal judge had ordered it to remove, not the entire stockpile, the governor said.

“They guaranteed him (Trump). They looked right at him and said, ‘It is moving out, and we have it under control,’” McMaster said, adding later: “It was a little bit, maybe, misleading.”

The agency, for its part, says it’s “accelerating efforts to remove plutonium from South Carolina.”

Nearly four months after Wilson suggested another lawsuit, there have been no settlement talks about moving the rest of the plutonium, according to a spokesman for the state attorney general’s office. And negotiations over the unpaid penalties have broken down, the state said in a legal filing last month.

The issue could remain unresolved for years. South Carolina is unlikely to sue until the deadline is officially broken on New Year’s Day, 2022.

“We don’t want the money. We want this stuff out,” McMaster said. “All of us involved will move heaven and Earth to see that it is not left here.”

The problem is that there are few places that can store the stockpile, and no state wants it.

The first court-ordered shipment of plutonium out of South Carolina triggered an uproar across the country earlier this year, highlighting the tightrope walk the federal government now faces.

The Energy Department quietly sent half a metric ton of plutonium to a huge complex in the desert of Nevada that’s best known for Area 51 and its history of nuclear bomb tests. It’s a place so remote and secretive that workers commute in and out on a government airline with flight attendants who have top-secret clearance.

Nevada sued when it got wind of the shipment, and the governor accused the feds of “completely unacceptable deception” when he learned it had already happened. The state’s leaders protested for months, and finally the agency promised not to send more.

Even so, Nevada hasn’t dropped its lawsuit because it insists it won’t become America’s plutonium dumping ground.

It says a promise isn’t enough.

Andrew Brown of The Post and Courier contributed to this report