“There are some new designs, but they are not demonstrably greater, so we are still dealing with the same exact issues,” said Samuel Hickey, a research analyst with the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation. “And realistically, we have a much better solution to the accumulation of spent nuclear fuel, and that is dilution and permanent geological disposal of waste.”

Also at issue is the potential that reprocessing of nuclear waste could undercut efforts to promote nonproliferation abroad.

By: Jeremy Dillon, E&E News reporter | eenews.net

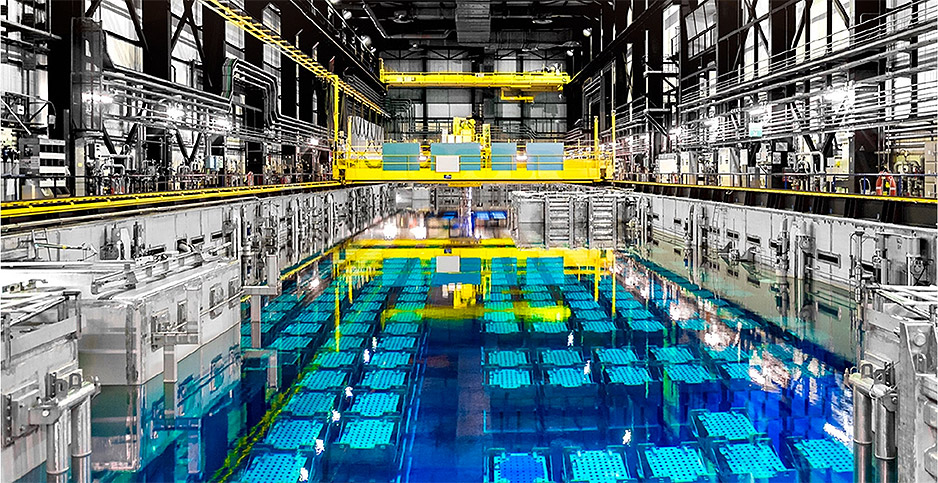

The nuclear industry’s push for the next generation of reactors is spurring a renewed look at reusing nuclear waste as reactor fuel, rather than burying it.

The implications of such a move have the potential to upend decades of nuclear waste management and global nonproliferation strategies. It also highlights a debate about safety and cost issues from recycling — longtime concerns that advocates say can be overcome.

“There’s no government policy decision that has to be made,” said Rod McCullum, senior director of used fuel and decommissioning with the Nuclear Energy Institute. “What has to be made is the business case, and what the advanced reactor developers are telling us is that they think there is a business case for using used fuel as the feedstock.”

The new push has in part been heralded by the Department of Energy’s assistant secretary for the Office of Nuclear Energy, Rita Baranwal, who in her first public remarks in taking over her position in 2019 expressed her interest in recycling or reprocessing spent fuel.

For Baranwal, the potential to expand past the 5% of energy used in the first cycle of uranium through a reactor presents an opportunity for the industry, especially as an alternative waste management strategy.

“It’s an avenue we are exploring at the moment,” Baranwal said during a May 1 virtual talk with the Atlantic Council. “I do think it is an option we should learn more about, and I’ve got a team of folks who are looking into it as an additional option.”

But much of the current worry stems from the conventional reprocessing of nuclear waste, a chemical process that removes plutonium from spent nuclear fuel for infusion into additional uranium for power use. Recycling — a term often used interchangeably with reprocessing — can also refer to the physical recovery of reusable materials from nuclear waste without the chemical effort.

The topic of reprocessing/recycling has been broached by every administration dating back to President Ford in the 1970s, with each one choosing to leave it off the table over cost and nonproliferation concerns.

Most recently, the George W. Bush administration in 2006 launched the Global Nuclear Energy Partnership, a program dedicated to exploring waste reprocessing’s potential.

The idea lost gusto during the 2008 financial crisis as the prospects for the nuclear industry suffered and the costs to build a reprocessing facility loomed over any project.

Obama administration officials briefly mentioned reprocessing as a nuclear waste disposal option following their move away from the proposed Yucca Mountain waste storage site in Nevada, but the idea never made inroads despite being used by several European nuclear powers as well as Japan and India. Members of the administration feared that such a waste management strategy could harm global nonproliferation efforts by adding another chemical step that could be commandeered for developing a weapons program or dirty bomb.

In comparison, the recycling of nuclear waste could avoid the perceived pitfalls of reprocessing, McCullum said. The process would require the reuse of used fuel with processing to get it back into a digestible form.

“This is a sea change,” McCullum added. “This is a completely different look at it for a completely different reason involving different technologies.”

Strange bedfellows

In addition to Trump administration actions, the possibility of recycling has caught the eyes of some climate-focused Democrats.

Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) has emerged as a key advocate for the process, especially for its potential to promote the deployment of advanced reactors. He has used two nuclear adjacent hearings in front of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee this year to make his case before Nuclear Regulatory Commission officials.

“The ability to repurpose this is incredibly valuable, and it creates a very important public purpose to what [the NRC is doing],” Whitehouse said during a March 4 oversight hearing for the top U.S. nuclear safety agency.

“This isn’t just the question of getting new reactors running,” he added. “This isn’t just the question of producing carbon-free power. This is also a very important question of seeking technological advancements that will give us a way to address our nuclear waste stockpile.”

Congress has started to express some research interest in the topic.

As part of the fiscal 2020 spending bill, appropriators directed DOE and the National Academy of Sciences to conduct a study of alternative fuel disposal options — among them, the prospect for recycling.

For Congress, recycling of waste could offer an off-ramp of sorts for its highly charged, decadeslong nuclear waste impasse that has left the United States without a tenable waste management strategy.

Advocates caution, though, that even with a recycling program, a permanent geologic repository is needed for final disposal of the nuclear waste. Critics of recycling have warned that traditional reprocessing techniques may bring more nuclear waste than simply storing used fuel.

Nonproliferation fears

Previous administrations have opted to refrain from reprocessing since Ford issued a policy statement against the practice in 1976.

For one, the cost of building a facility capable of reprocessing has given federal officials pause. Estimates from similar facilities in France and other countries have pegged the amount in the tens of billions to construct a single plant.

The United States had its own financial boondoggle in the now-shuttered Mixed Oxide (MOX) Fuel Fabrication Facility in South Carolina, which would have pursued a similar activity to reprocessing.

The MOX site was meant to turn the weapons-grade plutonium from decommissioned warheads into fuel sources for nuclear power plants. But cost overruns and construction delays made completing the project untenable, and both the Obama and Trump administrations moved to abandon the idea following a cost estimate that placed the total price tag in the $40 billion range.

Foes of reprocessing see similarities between such defunct nuclear designs and some of the advanced reactor technologies now under development.

“There are some new designs, but they are not demonstrably greater, so we are still dealing with the same exact issues,” said Samuel Hickey, a research analyst with the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation. “And realistically, we have a much better solution to the accumulation of spent nuclear fuel, and that is dilution and permanent geological disposal of waste.”

Also at issue is the potential that reprocessing of nuclear waste could undercut efforts to promote nonproliferation abroad.

Reprocessing relies on pulling plutonium out of used nuclear fuel and reinserting the highly radioactive material into new stock feeds. That additional exposure of plutonium leaves more opportunities for it to be used for nefarious reasons — be it the development of nuclear weapons or dirty bombs by foreign adversaries.

With the United States looking to increase the export of nuclear technologies abroad, the domestic reprocessing effort could undercut negotiations with countries like Saudi Arabia to limit the infrastructure for nuclear facilities that could be used to make weapons, critics warn.

Similar worries prompted the Carter administration to be the first to formally suspend reprocessing, an action that has prompted decades of policy fights about the technology.

“Every time we put the nail in this particular coffin, it keeps coming back up,” Hickey said.

NRC action

The surge in interest has nuclear advocates lobbying the NRC to take another look at the need for regulations surrounding the practice of recycling/reprocessing.

Currently, the NRC does not have a way to approve a facility to reprocess or recycle spent nuclear fuel. Such a pathway — likely the one major action needed by the federal government to greenlight the practice — is needed for industry to invest in the recycling advanced reactor concepts.

“This is about all we got, so please don’t let us down on that,” Whitehouse said on the need for the NRC to take up the issue.

Both the American Nuclear Society and Nuclear Energy Institute filed comments to the NRC at the end of May to urge the staff to pick back up a suspended rulemaking docket related to the topic.

That rulemaking was originally launched in response to industry interest in reprocessing at the end of the George W. Bush administration, when power providers were gearing up for a nuclear renaissance that never materialized.

In 2016, the commission moved to suspend the proceeding, citing lack of industry interest. NRC staff held a public meeting in March to hear comments on whether it should end the proceeding or take another look.

In response to that inquiry, the nuclear groups called for the NRC to consider the impact of advanced reactors instead of just focusing on reprocessing facilities.

“While no new reprocessing facilities are planned in the United States at this time, this in itself should not be the rationale for suspending rulemaking,” American Nuclear Society Executive Director Craig Piercy said in a May 28 request to the NRC.

He added, “Completing the reprocessing rulemaking would support future options for, and potential innovations toward, used fuel management as well as clean energy generation using advanced reactors.”