“Santa Fe residents would see shipments of plutonium trucked through the city’s southern edge if federal agencies carry out plans announced nearly a year ago.”

By Scott Wyland The Santa Fe New Mexican santafenewmexican.com

Santa Fe residents would see shipments of plutonium trucked through the city’s southern edge if federal agencies carry out plans announced nearly a year ago.

Santa Fe residents would see shipments of plutonium trucked through the city’s southern edge if federal agencies carry out plans announced nearly a year ago.

The prospect worries activists, local officials and some residents because plutonium is far more radioactive than the waste — contaminated gloves, equipment, clothing, soil and other materials — shipped from Los Alamos National Laboratory to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, an underground disposal site near Carlsbad.

The U.S. Department of Energy issued a notice of intent in December to begin the process for an environmental impact statement as one of the first steps toward diluting and disposing of plutonium left from the Cold War.

The notice hints that “downblending” the plutonium would be necessary to reduce radioactivity enough for the waste to be accepted at WIPP, which only takes low-level nuclear waste.

Opponents’ main concern is the 26 metric tons of cast-off plutonium bomb cores, or pits, that are being kept at the Pantex Plant in Amarillo, Texas.

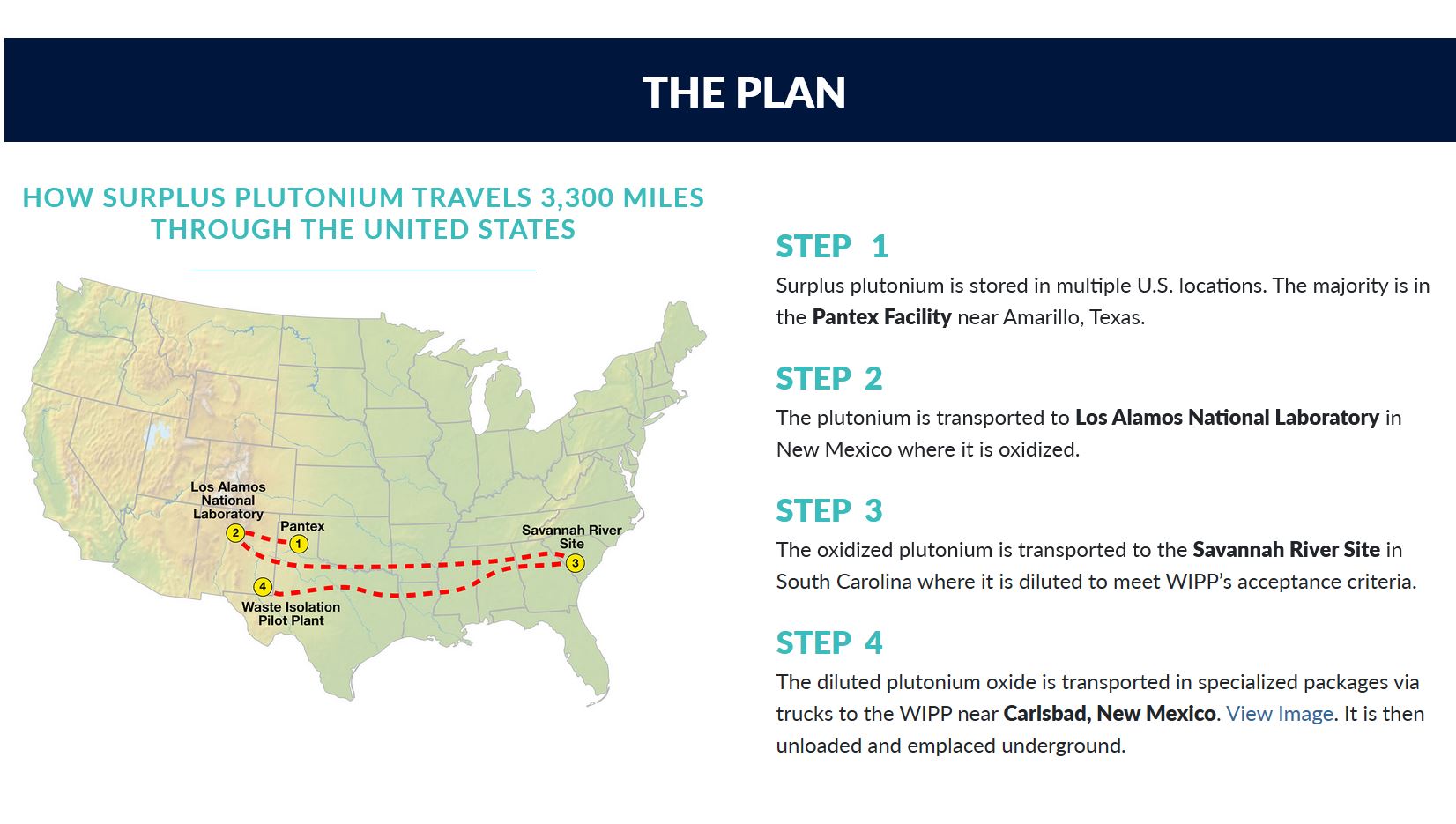

This plutonium would be sent to the Los Alamos lab where it would be turned into an oxide powder, and then the powder would be shipped to the Savannah River Site in South Carolina, where it would be further diluted before returning to New Mexico for storage at WIPP.

That would mean a more hazardous substance would be transported twice on N.M. 599 and U.S. 84/285 — when the plutonium comes in from Pantex and when the lab ships the powder, which can be highly toxic if released, said Cindy Weehler, who co-chairs the watchdog group 285 ALL.

“It will change the amount of transportation risk that we’re exposed to,” Weehler told an audience gathered for a town hall meeting Tuesday at the Nancy Rodriguez Community Center in Santa Fe.

The Energy Department is quietly putting these plans in place, Weehler said. She called the secrecy unacceptable, arguing people have a right to know if they’ll be at risk.

Agency officials didn’t respond to emailed questions on whether the Biden administration aims to move ahead with a Trump-era decision to dilute and dispose of the plutonium and, if so, what the timeline would be.

Although the agency is saying little about its plans, the National Academy of Sciences describes how the Cold War plutonium would be transported, reconstituted and disposed of at WIPP in its April 2020 analysis.

The lab is the only place where plutonium can be changed into a powdered form, and WIPP is the only site in the country that takes nuclear weapons waste, so the increased hauling of these materials through New Mexico would be unavoidable, said Don Hancock, director of nuclear waste safety for the nonprofit Southwest Research and Information Center.

“It’s disingenuous to say some of it might go someplace else when there is no someplace else,” Hancock said.

N.M. 599 was designed so nuclear materials being trucked to and from the lab would bypass the heart of Santa Fe.

But Weehler contends if a truck accident caused a breach in a container, it could still endanger some neighborhoods, especially if the plutonium powder is released.

The powder is toxic to breathe in — the fine grains can embed in the lungs, causing respiratory problems — and it can contaminate soil so extensively it’s impossible to purge, she said.

Aside from concerns about local communities, the plutonium will travel through a dozen states, totaling more than 3,000 miles, she said.

Santa Fe County Commissioner Anna Hansen, who helped organize the town hall meeting, said if the plutonium is going to be shipped to Savannah River, the federal government should build an East Coast repository for it instead of sending it back to New Mexico.

The federal government also should quit producing new plutonium pits, which will create even more waste that must be dealt with, Hansen said.

Eletha Trujillo, WIPP’s program manager, said the nuclear waste that’s transported in fortified containers known as TRUPACTs is extremely well protected.

The lids alone weigh 4,000 pounds each, making it virtually impossible for hijackers to gain access to the waste barrels, she said.

The trucks are set to go no faster than 65 mph to minimize the chances of a serious accident, Trujillo said, adding the trucks are constantly tracked and monitored.

“I know where every truck is in the U.S. if it’s leaving the WIPP site,” she said.

While the diluted plutonium shipped from Savannah River will be in those containers, Hancock said, the oxide powder departing from the Los Alamos lab will not.

The Energy Department originally sought to build a Savannah River facility that could turn Cold War plutonium into a mixed oxide fuel for commercial nuclear plants.

But after billions of dollars in cost overruns and years of delays, the Trump administration scrapped the project and decided to go with diluting and disposing of the waste. Meanwhile, plans call for turning Savannah River’s defunct mixed-oxide facility into a plutonium pit plant.

Hancock said there is no other method for getting rid of surplus plutonium, so Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm will likely stick with the plan she inherited.

Hansen said she would prefer if Los Alamos were not involved. And the federal government should find a way to dilute and dispose of the waste in one area rather than shipping it thousands of miles, which increases the chance of an accident, she said. “The more we move it around, the more danger we are projecting onto our citizens.”