Even though the first atomic bomb exploded in their state, New Mexicans were never compensated for the health consequences of nuclear contamination. These campaigners have vowed to change that.

By Sofia Martinez | The Nation thenation.com January 22, 2022

“It’s been over 75 years—we can’t wait anymore,” states Tina Cordova, cofounder of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium.

The group, which came together in 2005, is seeking environmental justice for the victims and survivors, called Downwinders, who were contaminated by the testing of the world’s first nuclear bomb on July 16, 1945. Its goal is to extend and expand the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA).

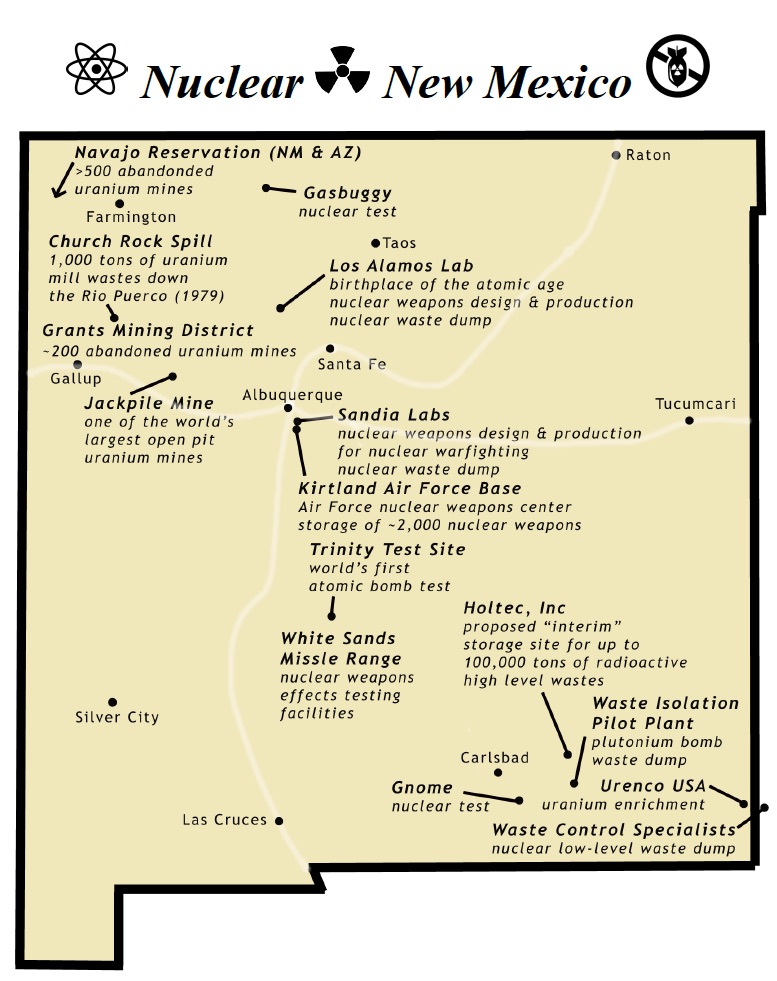

The RECA, which passed in 1990, will sunset in July of 2022. The act provides compensation and health benefits to uranium miners who worked in the industry prior to 1971 and former residents in parts of Nevada, Utah, and Arizona who lived downwind of the Nevada Test Site. However, even though the Trinity site—adjacent to White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico—was the first test of a nuclear bomb, the contamination of New Mexicans has never been recognized. The expansion of RECA would include New Mexico, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, and Guam, as well as the post-1971 uranium workers.

At a meeting held during an unseasonably warm November autumn afternoon in Albuquerque’s South Valley, Cordova and members of the organization address a group of organizers asking for support in their campaign. “It has been over 75 years and we have been suffering,” Cordova tells the crowd. “We were kept in the dark, lied to, and intentionally ignored. We deserve compensation for what our families have and continue to suffer.“ Cordova’s grandparents, parents, siblings, and extended family have suffered or died from a variety of cancers. Cordova too, is a survivor of thyroid cancer. She tells the organizers about the care that she provided her father, who suffered with throat cancer that progressed to his tongue and neck.

Although the US government knew about the danger posed by their bomb test, the residents of the area, most of whom are Chican@s/Latin@s with very long roots in the Tularosa Basin, were never told about the tests or informed about the risks to them, to their lands, or to their food and water supply. Residents found out only as they were awakened by a horrific blast that lit the early morning sky and experienced the subsequent radioactive white ash that fell over a 100-mile radius. Some said they thought it was “the end of the world!” Residents of the Basin and their way of life were forever changed. Their farm animals sickened and died from the contamination, warning the residents much like the proverbial canary in the coal mine.

The Tularosa Basin in south central New Mexico lies between several mountain ranges to the east and west. It is an endorheic basin—meaning very little water flows out of it. For decades, residents in the area had traditionally harvested water in outdoor cisterns that they used for their animals as well as their daily needs. The decision makers of the top-secret Manhattan Project gave little thought to these humble people, their land, their water, their way of life, or of the contaminated rain replete with ionizing radiation that fell on their bodies, their lands, and their water supply. These people were treated as dispensable, as the region was deemed “remote and uninhabited.”

The scientists working on the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, N.M., including their scientific leader Robert Oppenheimer, had underestimated the power they had created until after its detonation at the test site. The contamination from overexposure to the high levels of ionizing radiation has resulted in multigenerational cancers in the surrounding ranching families and residents of Carrizozo, Socorro, San Antonio, Tularosa, Roswell, and the broader Tularosa Basin. This test would ultimately lead to the first use of a nuclear weapon against a civilian population: the horrific bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Many New Mexicans consider their state the national sacrifice zone for the US nuclear arms industry. They feel that this targeting largely stems from environmental racism due to the state’s rural nature and significant populations of Indigenous and Chican@s/Latin@s peoples. They have suffered contamination from extensive uranium mining on Indigenous lands beginning in the 1930s—with thousands of uranium tailings and hundreds of abandoned mines still sitting on those lands—to the nuclear waste left behind from the Manhattan Project, to the siting in Carlsbad of the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP), the only operational deep depository for nuclear waste in the world. A nuclear enrichment plant run by Louisiana Energy Services, owned by the Urenco Group, has been operating in Eunice since 2010. The government is currently moving to accelerate plutonium pit production in Los Alamos despite numerous safety issues and antiquated facilities. The State Environment Department recently approved an expansion to the WIPP nuclear dump, though this decision is currently facing legal challenges. Another corporation, Holtec International, is seeking a permit to construct an interim storage facility for high-level spent nuclear fuel in the state.

The Downwinders have made state and national allies, garnering the support of their congressional representatives Senator Ben Ray Lujan and Representative Teresa Leger Fernandez. Leger Fernandez is a descendant of a Trinity Downwinder family and herself a cancer survivor. In September of 2021, the two of them introduced bills in the House and Senate to extend and expand RECA. On December 8, the House Judiciary Committee voted in a bipartisan fashion to support House Bill 5338, which would expand RECA coverage to the people of New Mexico and the post-1971 uranium workers. Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium members are hopeful that they might finally receive the restorative justice to which they are entitled, and they urge the public to encourage their congressional representatives to support the passage of these bills. They will need all the support they can gather to make certain Senate Bill S2798 also receives the same bipartisan support in the Senate. For more information about their work and how to support its efforts, please click here.